fruit of the mundane unrush

Music: Danny Paul Grody: In Search of Light (2011)

A couple of weeks ago a friend asked me how to make buttermilk biscuits, but we ran out of time. And when biscuits are the thing, taking one's time---and not worrying about getting flour everywhere---is crucial.

A couple of weeks ago a friend asked me how to make buttermilk biscuits, but we ran out of time. And when biscuits are the thing, taking one's time---and not worrying about getting flour everywhere---is crucial.

Biscuits are to be given away. One should never horde biscuits. It seems strange that whenever I make them, the twin panhandlers with the crooked knees, the doubles who stand like Cesare emerged from Dr. Caligari's cabinet, seem to appear at the median on Airport Boulevard near the Greyhound station. I never give them money, but frequently leftovers and often biscuits. The twins never appear together because they seem to be taking shifts. They share a bike. They seem grateful to get food. I always wonder what has happened to their legs, because they stand crookedly. They move slowly. I have never seen either of them ride that bike.

I've tinkered on my recipe for some years but have never written it down (it's a combination of Cooking Illustrated's "flaky biscuits" and Southern Living's "best buttermilk biscuits" recipes). I think that there are two secrets to good biscuits: (1) freezing the flour after you've cut in the leavening for fifteen to twenty minutes; and (2) not rushing it. Flakey biscuits are the consequence of leisure, the fruit of the mundane unrush.

As a young person I had more in common with the things strewn on the linoleum than the stuff on the tabletop. If I only knew then that one day I would like to cook I would have paid more attention, climbed up on a chair to see, even. I remember many bored, chilly Georgia mornings staring up at my grandmother's apron as she measured the ingredients for biscuits. Handfuls of this and that: flour, powder, shortening; sift it, roll it, lump it. Biscuits smell a certain homey way with shortening. Of course, trans fats are forever and coronary heart disease is ample testament to the fact, so one has to weigh the consequence of olfactory nostalgia: what price, that familiar smell?

Granny didn't cut her biscuits like I do (with a rocks glass, and without twisting); she made "drop biscuits" by creating mounds or lumps that came out, well, that came out with a perfect mix of flake and chew. I cannot replicate them. The recipe died with her. But mine are pretty good---that is, pretty and good---and they smell right.

What You'll Need: 2.5 cups of King Arthur unbleached all-purpose flour, and a few handfuls for dusting and kneading; 1 tablespoon of baking powder; ½ a tablespoon of baking soda; a pinch or two of kosher salt; 2 tablespoons of cold Crisco; 1 stick of cold butter; 1.25 cups of cold buttermilk. And coffee (for sipping while you make biscuits).

What You'll Need: 2.5 cups of King Arthur unbleached all-purpose flour, and a few handfuls for dusting and kneading; 1 tablespoon of baking powder; ½ a tablespoon of baking soda; a pinch or two of kosher salt; 2 tablespoons of cold Crisco; 1 stick of cold butter; 1.25 cups of cold buttermilk. And coffee (for sipping while you make biscuits).

"I am in the kitchen in a double-wide facing a stove and oven. The stove/oven is candy-apple red, from the 1950s, and I recognize it is one that my friends Gary and Trish resorted and have in their real, dreamy kitchen, except in the dream it belongs to my parents. My parents don't really use it, but I like to. To my right is breakfast bar and past that is the living room and two reclining chairs where my mother and father lounge watching a morning news program. There is a protective, plastic covering on the recliners, and when my parents move they squeak. I am kneading and folding dough to make biscuits."

"Go on." "Hmm. Making your parents "Don't you think that's too easy an interpretation, though, too much of a softball?"

"Funny word, softball. Biscuits. Makes me think of---" "---I know. And I'm a housewife for my parents, the anima anxiety of an only child. If I can't make 'em babies, I'll make 'em biscuits, dammit!" "I am worried that the biscuits won't turn out right, you know, turn out like my grandmother used to make them. I don't want to disappoint my parents. I think I'm wearing an apron that someone made for me, maybe my granny, I cannot remember. And as I make the biscuits I start to think about how I am becoming the parent now and the struggle of my generation---the exes---and how we are depending on our parents well into our 30s, but here I am this once cooking for them. I don't know if, in the dream, I am visiting or if I am living with my parents again. Still, there's much more at stake than making breakfast."

"I am worried that the biscuits won't turn out right, you know, turn out like my grandmother used to make them. I don't want to disappoint my parents. I think I'm wearing an apron that someone made for me, maybe my granny, I cannot remember. And as I make the biscuits I start to think about how I am becoming the parent now and the struggle of my generation---the exes---and how we are depending on our parents well into our 30s, but here I am this once cooking for them. I don't know if, in the dream, I am visiting or if I am living with my parents again. Still, there's much more at stake than making breakfast."

Then, stick the bowl in the freezer for twenty minutes. Seriously: in. the. freezer.

Then, stick the bowl in the freezer for twenty minutes. Seriously: in. the. freezer.

Jack Spicer drank himself to death by the age of forty, which is too bad. Among many things, like media technologies and magic, he wrote of the sporting life, because he started-out as a linguist unsullied by deep structures of Chom(p)sky. From his final collection titled Language: "The poet is a radio. The poet is a liar. The poet is a counter-punching radio./And those messages (God would not damn them) do not even/know they are champions." He wrestled with the word, a lot you know, even giving himself the one-over; the booze was really just lube, in the end, but there's a point at which you need the friction to re-member. All that forgetting gets you somewhere, you bet, but it's not the kitchen.

Do you know Floyd Kramer? Still, I see myself cutting butter with the women rather than in a recliner next to cousins and uncles watching a match. (Counterpunch.) On Thanksgiving holidays, when I grew old enough to understand the division of social favor, I knew my assigned place was watching football on the floor with the boys while the girls confabbed in the kitchen. Nothing was more boring than watching football on the floor. I would have rather watched my grandmother make meringue, even though that was almost as tedious as the Atlanta Falcons. To this day I don't care to eat either of them. Still, the shortwave radio was in the kitchen, and I liked to play with its knobs. Jesus sermons and Floyd Kramer, and warble inbetween their stations climbing that amplitude.

Still, I see myself cutting butter with the women rather than in a recliner next to cousins and uncles watching a match. (Counterpunch.) On Thanksgiving holidays, when I grew old enough to understand the division of social favor, I knew my assigned place was watching football on the floor with the boys while the girls confabbed in the kitchen. Nothing was more boring than watching football on the floor. I would have rather watched my grandmother make meringue, even though that was almost as tedious as the Atlanta Falcons. To this day I don't care to eat either of them. Still, the shortwave radio was in the kitchen, and I liked to play with its knobs. Jesus sermons and Floyd Kramer, and warble inbetween their stations climbing that amplitude.

Step Two: remove the flour-leavened freeze and add the buttermilk to the bowl and, with a spatula or fork or your fingers, get the stuff into a sticky ball. Dump the ball on a pile of flour and, with a well dusted French rolling pin (much better than the American flat roller, which gives you little to no real control or feeling---manual or automatic?) flatten the ball into a rectangle. Then, fold the dough like a business letter (twice from each side), turn 90 degrees, flatten. Only do this one or two more times---if you fold and flatten too much the dough won't rise into flakey layers. Using a rocks glass or biscuit cutter, cut your biscuits and put them in rows on an ungreased cookie sheet.

Step Two: remove the flour-leavened freeze and add the buttermilk to the bowl and, with a spatula or fork or your fingers, get the stuff into a sticky ball. Dump the ball on a pile of flour and, with a well dusted French rolling pin (much better than the American flat roller, which gives you little to no real control or feeling---manual or automatic?) flatten the ball into a rectangle. Then, fold the dough like a business letter (twice from each side), turn 90 degrees, flatten. Only do this one or two more times---if you fold and flatten too much the dough won't rise into flakey layers. Using a rocks glass or biscuit cutter, cut your biscuits and put them in rows on an ungreased cookie sheet.

Step Three: Brush those puppies with some melted butter (about a tablespoon and a half) and bake at 450 for about fifteen minutes or so. After browned on top, take them out and brush with any remaining melted butter you have and let them sit for about seven or ten minutes before serving.

Step Three: Brush those puppies with some melted butter (about a tablespoon and a half) and bake at 450 for about fifteen minutes or so. After browned on top, take them out and brush with any remaining melted butter you have and let them sit for about seven or ten minutes before serving.

Here's a gallery of the most recent biscuit-making session. I didn't make them for anyone, really, just sensed I should make them. Because . . .

I wrote though Thanksgiving, for the most part. Mostly. At the special moment, about one in the afternoon to the ambient blares of referees whistling, I remembered the boys would be summoned and lumber into my grandmother's tiny kitchen and she would "say grace." Always the same, patterned grace, about nourishing bodies and soldiers doing something over there. What is Thanksgiving, really, without young people from the lower classes fighting a war for someone else? (Sucker punch.) Always a war, about who wears the apron and who wears the helmet.

The handwriting of the found list resembled that of people from my grandparent's generation. Granny had no use for round biscuit pans because she dropped hers, on a cookie sheet. Times were tight and tough and I can still remember finding books and books of unused S&H green stamps in one of her desk drawers. At the bottom of the "found object" blog is Spicer's famous "Letter to Lorca" from 1957, where he instructs the other poet's poet on fetching the alive from the "garbage of the real," the garbage of the visible or picture or image, because "that is how we dead men write to each other."  I stumbled across another "found object" blog. Someone discovered a note from his or her father's desk, a list of "to buy" items for the first, new apartment with mom, penned before she was conceived (or, at least, was gestating). A plate. A sink stopper. A jigger, for Manhattans she supposes. She doesn't know what a Pyrex dish is---but isn't this essential, even today, for everyone's first apartment? She also doesn't know that a biscuit pan is (or used to be) round.

I stumbled across another "found object" blog. Someone discovered a note from his or her father's desk, a list of "to buy" items for the first, new apartment with mom, penned before she was conceived (or, at least, was gestating). A plate. A sink stopper. A jigger, for Manhattans she supposes. She doesn't know what a Pyrex dish is---but isn't this essential, even today, for everyone's first apartment? She also doesn't know that a biscuit pan is (or used to be) round.

it's squander-and-shit friday!

on gratitude

Music: Steve Hauschildt: Tragedy & Geometry (2011)

The machine, the box with blackface and red led numbers and lights, beeped incessantly, the sort of pressing electronic screech that refuses to let you make a pattern in the sound, that willful sonic moiré that comforts; the peace of a patterned rhythm.

"Do you have someone to call, a significant other or loved one?"

"No, not in this state."

"A friend?"

"Well, yeah. But everyone's at work."

"If you have someone to call, now is the time. We'd like someone to be here when you come out of anesthesia."

"You're going to operate?"

"It's likely. This is the time to have someone here."

Three years ago the nurse's certitude was, in the end, thankfully dismantled with an exception. I didn't have the operation. Hours later, the screech was replaced by a rhythm, not of beeps, but of the shuffling feet of friends in and out of a antiseptic room. Friends who, I hope, never get see my hair that dirty again.

I am thankful for my loved ones who are determined to make rhythms and forge patterns out in the blaring-Nons of the past, and the gaping nothings sure to come. Without you, I'm just a dead turkey.

separation anxiety

Music: Active Child: You Are All I See (2011)

Five days in a city that loves, that doesn't loathe as a matter of habit, thriving on an industry that turns on a suspension of surveillance and ample chers and darlins and babys like gravy, can make you wonder what you've traded in for health and regulated rhythms and a steady job. At least for a few days. New Orleans can get in your blood, and not like Las Vegas or Orlando like some forced, Oliver Stone virus of paranoid hedonism or policed happiness respectively (fantasies of blind enjoyment, foreplayed disordered order), but a dis-ease of tolerance. A temporary disease-cum-ease, at least: "I can't believe it took us an hour for coffee," I found myself saying to friend after a sojourn in search of coffee. "I can't believe I just complained about that," I said to myself quietly, angry at my complaint. "This is Louisiana." I should know better; I should listen to the rhythms I once felt living in the state (-of mind). I came around, eventually. And just when I let it in and was ready to stay forever, it was time to go.

It's easy to find solace in cynicism, and I've got barnacles of the stuff encrusted on any number of cognitions and nerves, some sad ganglia in the groin too. But I do love New Orleans; I love that there is soul somewhere in that tourism, something deeper than slot machines or a desert or . . . blue-dyed water. . I love Chicago and Denver and New Orleans. And parts of Maine. I love the creek bed behind mind grandmother's house that is now squatted by a strip-malled grocery store. I will let myself love some cities and places and not be clever about the beloved. It's permissible to love a place crammed with people, even. And there is something in a people or their vibrancy released of the usual or mundane orders that is genuine, even when a dollar is crammed in a shoe resigned or habituated to dancing.

New Orleans was a comfortable lap (at least for me) for seating a conference, the strangest of things that professions and politics have created and attended, this weird, mondo-klatch designed for the visual spectacle of a particular economy (of knowledge, of power, of money, of unrealized sex).

As I do this gig more and more, I find myself enjoying, increasingly, those who dress well---and I mean that in many senses. If ideas are attractive, why not align the senses "all the way down?" It's a military fashion show, you know? (a very crypted musical nod, I know.) And this in a city that rewards stylistic risk coupled with a relaxing of the defenses. The cultural context made it easier for me, this time, to detach a bit and observe and enjoy the conference for what it seems to be for me at this moment of my career, which is now fully woven into my life, and that's a life that cannot be fulfilled by a career but which is enriched by it nonetheless: a conference is a huge, ever pulsating brain that rules from the centre of the ultraworld.

That much, that last bit, is also musical joke that has an idiosyncratic relation in my mind to Hegel's understanding of the "world spirit." (I really don't know what Paterson means by "the ultraworld," though I'm pretty sure LSD was at one point involved in the coin.) The association is neither here nor there for you nor important except for the weird realization for many of us that conferences are not only economies of exchange but organisms that reckon with change---with mortality. When I started attending them as a graduate student, I viewed the academic conference as a smorgasboard of "free" (though ot really free) food and booze and a kind of star system that circulated celestial bodies. The annual National Communication Association meeting is certainly that---in so many ways---but from the vantage of middle age no longer in the same way I had supposed. Some years ago I started to recognize the heart of the pulsation shifted to something memorial, a kind of life-tracking device functioning centrally for some and peripherally for others, but functioning just the same: multiple cohorts are growing old together and using the conference as a way to re-member and re-center over the auspice of the idea.

The promise of the auspice is often (if not routinely, as a matter of mutation) perverted. This is the function and dynamic of governance, to argue over the character of the mutation; for example, the administration inevitably emerges at variance with the membership. As with the rave or circuit party, so with the professional convention The Burkean barnyard bubbles up, often over the spectacle of policy, this year in the name of "civility" or less publically, crass careerism and stupidity, then (re-membering) last year prestige, next year I predict entitled nihilism or apocalypticism (the jargon of the meta-meta, matta matta . . . or as I overheard a senior scholar intone this morning, the excluded third or "turd"). But this ironically consequential prattle really runs cover for the maturing attendee, for the central conversational labor: we are growing older, wending toward a dying, and we want to matter, at least to each other. Growing old together. Children produced and reared/books seemed to dominate our conversations.

My friends and I talked repeatedly about petered partying. About not going out to drink. About staying in, getting rest. About tiring over the reindeer games.

Conferences are machines of recognition. The observation seems trite, I know, but in the setting of New Orleans this demand really was starker and more interesting to me, even fascinating because of the mood that this particular city inspires, a mood of cutting through the crap, almost like a high school reunion in a decade or two after the graduation year: how complex have ways become to ask for love and to say to others "you are loved?" Conferences are combines---projection zones and screens, and its off-sites and friend-only dinners and no-hosts spaces of relational identification (against).

"But, I phoned ahead and they said there was space for 200."

"Yeah, but you didn't expect 400 to show up," he responded. Overhead.

Underestimated. There is a "soul" to this, after all.

There are many stories to tell, and three, overly-disclosive paragraphs that I have just deleted.

Still, what a strange and beautiful thing this last conference was. I will be thinking-through its experiences for some time to come. I suppose my point here is that I think many of us who went to the conference assume, going to a professional meeting, that these are professional endurances. That is, well, that is the rhetoric we produce about them (as I said, "Ugh. And so the circus begins.") But deep down you and I know---the you who know me through school---we know that these things are major life events, extremely significant, sometimes potentially traumatic and increasingly operatic. As an academic, we have to reckon with the fact that we invest so much in our professional lives that it becomes central to our lives---and this is why location, mood, and the rhythms of the host city are so important.

Perhaps this is why so many of us were talking about, feeling about, how much this particular conference in New Orleans was good and moving and loving and important. The fantasies of the city were implicated---I don't think superficially---in our conference experience, in the traumatic and deeply consequential event of Katrina and the disastrous Nation State's response to it and our feelings about ourselves and this city and its mood and our orientation to recognition. And why so many of us want to avoid the conference next year in Orlando. It's as if our personal lives and self-conceptions are at stake. It's like Disney makes plain the necessary economy of professional fantasy and all the work it actually does to allow us to do the labor of loving we all really want. We don't want to see those we love and respect in a strip mall.

I didn't get to spend time with those whom I admire and love and respect enough in these past days. I left wanting and I felt guilty for not seeing or doing this or that thing with loved ones. But that is a good wanting, I think, and it says something about the import of a city and its soul and its dispositional seat. It says something about my not wanting to go to a conference in Orlando, Florida, as if my time with the admired and loved would be cheapened by the con- and pretext. That the auspice of the idea would be somehow cheapened by completely retreating the necessity of the spectacle and the dollar (a observation I would make similarly about Las Vegas).

Still, these unordered musings begin, for me, the thinking of bodies in place. It's not something I've really dwelled on in the past, since my focus as been on the moorings of professional stability, which do not so much depend (at least initially) on place. I've chosen a line of work for which the choice of rest is not mine. Even so, seated in a city I love (Austin, indeed!), I recognize that place (geographical culture) now has a purchase on me it hasn't had before---at least consciously. Travel has a new meaning. And I'm starting to reckon with that in ways I've never really done before. This is, I think, a dimension of the subjectivity of settling, of emplacement. Of disposition.

I'm realizing, I guess, that where I meet my far-flung friends has an impact on relational contact, on professional stead, and the situation of stranger encounter.

a tale of two perversions

Music: Georgia Fair: All Through Winter (2011)

For the intellectual heir of Jacques Lacan in France, Jacques-Alain Miller, "perversion is when you do not ask for permission." Such and observation is shorthand for a distinction between jouissance, human enjoyment or a kind of pleasurable pain impervious to or beyond representation, and desire, which is founded on a question (what do you want? what do I want?). Perversion is characterized by a relative disinterest in others, only the act---a kind of pure act---that invites charges of obscenity. Perversion calls the law, broadly conceived, into being; where there is perversion, there is discipline . . . there is a spanking, and increasingly perverse spankings are becoming public. Spankings are delivered along the inseam of permission and permissibility: For example, in Mike Nichols' 1967 masterpiece The Graduate, Ben comes to realize his desire at the moment his seducer appears to transgress the rules without asking. "For god's sake, Mrs. Robinson. Here we are. You got me into your house. You give me a drink. You . . . put on music. Now you start opening your personal life to me and tell me your husband won't be home for hours."

For the intellectual heir of Jacques Lacan in France, Jacques-Alain Miller, "perversion is when you do not ask for permission." Such and observation is shorthand for a distinction between jouissance, human enjoyment or a kind of pleasurable pain impervious to or beyond representation, and desire, which is founded on a question (what do you want? what do I want?). Perversion is characterized by a relative disinterest in others, only the act---a kind of pure act---that invites charges of obscenity. Perversion calls the law, broadly conceived, into being; where there is perversion, there is discipline . . . there is a spanking, and increasingly perverse spankings are becoming public. Spankings are delivered along the inseam of permission and permissibility: For example, in Mike Nichols' 1967 masterpiece The Graduate, Ben comes to realize his desire at the moment his seducer appears to transgress the rules without asking. "For god's sake, Mrs. Robinson. Here we are. You got me into your house. You give me a drink. You . . . put on music. Now you start opening your personal life to me and tell me your husband won't be home for hours."

Mrs. Robinson: "So?"

Benjamin: "Mrs. Robinson, you're trying to seduce me."

Mrs. Robinson: "[chuckles] Huh?"

Benjamin: "Aren't you?"

Despite George Michael's claim that "everyone wants a lover like that," it's true in the diegesis only for Bancroft's brilliantly played character. The spectator identifies with Ben's desire ("is this what I want? do I like this?") as Mrs. Robinson appears to enjoy his questioning (much more than any sex act; it's not about sex, or rather, it is about sex but not concerned with the sex act). In this way the perverse act is staged for us in cinematic fantasy: it's not that Mrs. Robinson truly wants Ben to make love to her; rather, it's Ben's reaction and attempts to bring the rules to bear on the situation: this is not supposed to happen; this is inappropriate; this is wrong. What Lacan teaches us about perversion is that Mrs. Robinson is not enjoying the promise of seduction, but the staging of the wrong itself. Sexual pleasure, if it occurs, would be incidental, a spin-off like Tang for space exploration. Indeed, from the perspective of the pervert, Mrs. Robinson is only bringing about Ben's enjoyment of her, beyond his desire, and is in some sense envious of the desire (that this, the questioning) he has in the moment. Strangely, desiring is a kind of limitation, it puts guardrails on enjoyment, it helps us to "pull back." Mrs. Robinson cannot "pull back," and despite appearances, is at some level envious of those who can question and forge limitations, like Ben. And at the same time, she sees herself as channeling his enjoyment---that which is presumably associated with the rules, that which is presumably open to her because the guardrails are off.

This week, given the priapic plights staged by Penn State: The Movie, for the thinker interested in psychoanalysis commentary almost seems compulsory. The topic of pedophilia, however, strikes at the heart of psychoanalytic understanding and locates psychoanalysis' rhetorical weak-spot: in providing an explanation for the violation of our most taboo of cultural taboos, those relatively unsympathetic to psychoanalytic insights can easily find such insights morally objectionable themselves. Or, to put it plainly: it's taboo to talk about the taboo. Discussions of pedophilia that say too much---that say something other than blanket condemnation---are somehow odd apologias for perversions, or participate in scope of perversion itself. That, too, is true, hence the title of this post. And the strategy of approaching the issue of perversity obliquely, at a slant, is for good reason ,because talking about the taboo similarly courts misunderstanding if not outright condemnation.

Unless, of course, one is a "journalist."

Indeed, the overdetermined, culturally sanctioned way to discuss perversion is perverse itself: to discourse on pedophilia, I must first and foremost condemn it in the name of human decency. This is not to say I don't agree with the spirit of condemnation. Although I would stop short of pathologizing perversity as such, pedophilia is culturally forbidden form of perversion because it is morally reprehensible, and for reasons easily adduced, principled and consequentialist. Even so, this obligatory opening gesture ("pedophilia is evil!") is itself perverse if one understands perversity is also, first and foremost, wrapped-up in a complicated relationship between jouissance and the law. Two quick examples will suffice, the first from my own recent past experience as a scholar.

Some years ago I was a blind reviewer for a manuscript that purported to be a content analysis of the website of a famous pedophile/pederasty advocacy organization. The conclusions of the analysis were, it seemed to me, obvious: the website's rhetoric made claims about the "rights" and civil interests of boys, who have been systematically disempowered in Western culture, and this organization promoted and protected boy's rights. The arguments made by the website were consistent with the defensive claims of pedophiles with one exception (that children are seducers, a common claim made by pedophiles). I rejected the manuscript on scholarly and moral grounds. As scholarship, the essay seemed rather pointless. But the essay was not pointless in other ways; the moral objection I raised was that the point of the scholarship seemed to be its motive,enjoyment. The authors were "getting off" on slumming around in pedophiliac rhetoric. For the authors, despite a sense of detached scholarly objectivity, the motive deployed to justify such "research' was moral: "we have to understand how perverts think in order to stop perversity!"

The irony of my rejection of the manuscript was that it was particularly righteous (the editor never asked me to review a manuscript again because of this righteousness). We might even say that I took some pleasure in naming and denouncing the enjoyment of others as obscene; in castigating what I saw as a perversion of scholarly mission I was, in my own way, also engaging in a kind of perverse enjoyment---I got to embody "the law" and deliver the judgment of indiscretion and moral violation. And that observation begs the second example easily, NBC's pedophile-busting reality television program, To Catch a Predator.

For about three years (2004-2007), show host Chris Hansen made his a household name by busting would-be sexual predators lured to parentless homes by of-age teens or young adults pretending to be 12-14 year olds. For me, the show was excruciating to watch for a number of reasons, but the most glaring was the obscene enjoyment of Chris Hansen himself, visibly delighting in the painful righteousness of meting the moral law (which, viewers were told, were followed by the police after Hansen got to confront the "suspect" on camera). Despite ratings, the show was eventually cancelled because, NBC claimed, "sexual predators" were now well aware of the show and its methods and were becoming harder to "catch." I think the show was cancelled because of the mounting criticism and, in my view, its fundamental obscene character. The show was inescapably perverse in its staging of a sado-masochistic reality: the sadistic predator is revealed to be a masochist, Hansen becomes the law-giving sadist, and so on. Perhaps the most disturbing detail here is that the decoys were of legal age, entrapping rhetoric to the contrary, and although few will admit it, often times the spectator felt sorry for the would-be criminal! Therein is the complexity of perversion as cultural entertainment (examples abound in horror films that get us to feel something for the evil anti-heroes).

These examples---of film, of scholarly blind review, of To Catch a Predator---represent perverse acts on both sides, behaviors that are classically perverse because they are premised on a kind of unwavering faith in either the jouissance of the Other or the Law (I'm only doing what you want me to do; I'm only following orders). I hope they serve to illustrate how all of us are capable of obscene enjoyments, how we all can do perverse things or participate in the perverse. Such daily perversities, however, are premised on behaviors and nothing fundamentally essential. There are some people in our society whose subjectivity is perverse, however. These folks are very rare. And in psychoanalysis, these are the folks we say harbor a "perverse structure." All people are capable of perverse acts; a very few number of people are themselves perverse. The pedophile is the most stark example of an individual for whom perversity is a core disposition.

Of course, space prevents any thorough or technical discussion of perversity as a structure that is, in rare cases, pathological. Pedophilia is perhaps one of the most vexing "diagnoses," since most people do not have the capacity to understand it in an empathetic way, and this is because we are structurally "neurotic." Here's a quick thumbnail of the Lacanian take on the perverse structure: most people, paradigm persons, undergo two processes or formative transformations in childhood, "alienation" and then "separation." Collectively these fly under the term "castration," which in general just means having one's self "cut off" from the mother-child dyad as one unit, becoming "two" (or really, becoming "three," since the mechanism of the cut off is a third other).

According to Lacan, each process or, better, "event," concerns a symbolic paternal figure (a second parent, irrelevant of sex, can function as the "symbolic father"). The first process, "alienation," is when a child learns that he or she is not the same being as his or her mother and, more importantly, that s/he is not supposed to be or allowed to be. It is the moment of hearing "no" and understanding what it means for the first time---coming to terms with Jagger's observation that you cannot always get or have what you want. To be alienated is to understand prohibition, to understand what "no" means.

Understanding "no," however, doesn't necessarily mean you'll mind the prohibition. Of course, because the "no" is usually scary or accompanied by a threat, most children do. Minding the prohibition, accepting it, is the second step termed "separation." We've all seen this with "separation anxiety" in toddlers, yes? There are certain kids that cannot possibly part with mama. Kindergarten is, in many senses, a pedagogy of separation (and this, of course, requires the life-skill of sharing). It is with the understanding that comes with separation and absence that we learn the basic life-skills of exchange and substitution. So, for example, take the Peanuts character Linus: he cannot part with his safety blanket and sucks his thumb. These are substitutions, or transitional objects, that presumably help him to deal with a separation from mother or the maternal body. Regardless, the end result of successful separation is symbolization, fundamentally an economic relation premised on substitution (exchange, transaction, etc.). And for Lacan, the symbolic is the law as such, broadly construed.

Most of us are neurotics: whether obsessive (most academics) or hysterical, neurotics have undergone both alienation and separation. Together, these events mark the completion of "castration," whereby one is prohibited and separated from the maternal bosom and thrust into the world of social (or symbolic) relations. Prohibition, that initial "NO!" asks us to give up our unbridled enjoyment of mama in exchange from something else---the symbolic world represented by speech. Desire comes into play at this point in terms of questioning: "Ok, I cannot have mamma for myself. What, then, do you want from me? What do I want?" Without language, we cannot reflect on what it is that we desire. Enjoyment represents the satisfaction of our drives---eating, shitting, screwing, touching ourselves---and these things we learn we cannot do whenever we want. We give up our driven impulses with a little self-restraint to be social creatures, and "let go" only in socially sanctioned ways. Desire functions, in a way, as a limit to enjoyment; the guardrails, as it were.

Now, the psychotic person never goes through alienation or separation; this is a person who never understood "no." Psychotics are often very easy to spot (especially if you do any sort of online dating!). The trickier character is the pervert. The pervert is in a kind of developmental purgatory or limbo (although I wince at using that d-word): she has heard and understood the prohibition of alienation, she gets the "no," however, she has no way of symbolizing it or understanding (internalizing) its meaning. This is why structural perverts are very good at leading what appears to be a "normal life," indeed, why some may never commit perverse acts: law is reckoned with, it is felt, it's just not established or firmly emplaced. To use a computing metaphor: it's like knowing how to code HTML, just not being able to do it or not seeing where you've missed the backslash or typed the wrong coding. Or rather, it's being able to follow the rules perfectly but not really caring about the end result; it's following the rules/code itself gets repeated, over and over, almost compulsively.

There's a lot I'm not going into here (for example, the symbolization of the "maternal phallus" in the fetish, the realization of "lack," and so on), but the gist, I hope, is clear: the pervert can enjoy but cannot desire because s/he lacks the symbolic resources to desire. The pervert does not ask questions, or as Miller puts it, "does not ask for permission." And so the pedophile emerges as a person who knows, very well, that what he or she is doing is not socially sanctioned, appropriate, and so forth, but does it anyway---not because it is taboo, but rather, to bring the taboo into being. What's at stake for the pervert is the law itself, the law as such, the invitation for the paternal, a deep call for understanding, at some level, what the "no" means or is because s/he cannot.

Sandusky is not only a textbook case of pedophilia from the behavioral (viz., DSM) standpoint, but from a Lacanian standpoint was well. He went to great, elaborate lengths to create an environment for his victims---troubled boys whom, predictably, are looking for father figures, who themselves are calling out for the alienation/separation of primary and secondary repression. From the pervert's standpoint, he is doing what the child wants, bringing the law into being. This is why, according to Fink, the cultural fantasies of unbridled enjoyment are really a ruse for the pervert and the horrified observer: Sandusky is racked with anxiety, and by repeatedly restaging the trauma of prohibition he is making the Other---the Law---exist. That he may "get off" in the company of the boys is really not the purpose; however strangely, the pedophile sees himself as a liberator, letting boys enjoy themselves. Yes, this is twisted, but it's only this twisted thinking/feeling that begins to explain the compulsory character of perverted acts (I would be remiss not to point out that there is also some empirical brain research that suggests there are serious differences in the brains of pedophiles, but what that means exactly is not yet understood or proven in any satisfying way).

I've gone into the differences between structural perversion and perverse acts because one can beg the other. Often, our response to perverts is also similarly perverse, and I think we would do well to recognize the point of convergence in righteousness and our rush to absolute condemnation and judgment. As Size (damn autocorrect) Zizek notes of "fundamentalists" in his recent How to Read Lacan, the religious zealot's conviction "does not concern facts, but gives expression to an unconditional ethical commitment." That unconditional, blind commitment to some principle or law is perverse because at its core is a sort of painful delight---enjoyment---in proclaiming the law, thou shalt not! It's Chris Hansen busting would-be sexual predators, or my blind-reviewing self condemning scholarship as trash. It's the subtext of the current media orgy reporting on and condemning, in nauseating detail, the crimes committed by Sandusky and, we worry, school administrators in covering it up: in the zeal to win at any cost, the "perverse core" of collegiate athletics is revealed in its complicity with the obscene and heinous.

The two perversions, then, are these: the perverse structure of pedophiliac subjectivity, and the perverse response we have to that subject. One begets the other. One kind we might feel is justified---and frankly, it is. But we should not ignore our own complicity in this strange, warped economy that would keep enjoyment at bay, since the very fantasy of "busting a pedophile" allows us to approach enjoyment just the same, albeit from a different direction, from the higher ground of moral righteousness. This is, of course, not to excuse or condone either type of perversion. It is to say, however, that we need to be more critical of our consumption of this story---and the zeal with which is it being covered. We cannot help ourselves, like watching the scene of a car accident. But, still, I guess I'm saying we should not exempt ourselves from obscenity at the heart of controversy. Again, I come back to Jagger: "I shouted out/ who killed the Kenndys/ when after all/ it was you and me." One is right to be suspicious of those who proclaim most righteously the evils of Sandusky, just as we are the religious zealot who condemns "fags" to hell. Sandusky will be brought to justice, I just want us to be wary of how much we ourselves enjoy seeing that. It too easily can snowball into a moral panic (pedophiles under every shrub) or righteous movements that create even more victims.

At the risk of perversity, here's the moral: Dehumanization is the most terrible perversity of them all. Or, you know: two wrongs don't make a right.

it's synth-pop friday!

on misogyny and "the black man's hour"

Music: Sigur Ros: Inni (2011)

A forth woman will step forward today to report that she was sexually harassed by a presidential candidate at 1:30 p.m. A friend and colleague at another university alerted me that she was expecting a term paper today from a student who would be arguing that this candidate is a "victim." This news got me to thinking about Susan B. Anthony.

A forth woman will step forward today to report that she was sexually harassed by a presidential candidate at 1:30 p.m. A friend and colleague at another university alerted me that she was expecting a term paper today from a student who would be arguing that this candidate is a "victim." This news got me to thinking about Susan B. Anthony.

As is well known---er, except, perhaps, by public high school students in Texas---black male suffrage was established in the 1870s with the 15th amendment. Support for the amendment split the "first wave" feminists into two camps: those who refused to lend their voices to the reconstruction legislation because it did not extend suffrage to all and those who supported the amendment as a kind of incremental progress toward universal equality before the law. These divided efforts would also split into federally focused and state focused strategies for women's suffrage. It would take over another forty years to establish women's right to vote in the United States with the 19th amendment (and shortly thereafter, establish an age requirement for voting too).

Anthony and Stanton's famous opposition to the fifteenth was met by other voices, many suffragists but also a number of vocal misogynists, that it was "the black man's hour," meaning that women should "wait" until their proper time. In hindsight, of course, it's easy to argue such arguments were shortsighted, however, we have to remember that each historical moment is more complicated and knotty when viewed from the crises of the future. After the Civil War, one can only imagine that in the late 1860s either a state or federal approach seemed viable---we celebrate all the suffragists for their strivings. Ultimately Anthony and Stanton were right (on political, legal, cultural, and theoretical grounds), but that's not to discount those suffragists who agreed with the strategy of incremental progress: they took that inch, and although it took too long, the mile eventually came.

Today the phrase "black man's hour" can be understood as shorthand for the ideology that underwrites it: the superiority of the male sex and gender and the secondary station of woman, whether "natural" or "cultural." Even writing such a statement seems absurd, and yet, we can certainly discern the ideology at work in contemporary politics: taking the admittedly facile representations of the mainstream media as a symptom, on the right, "black man's hour" references a commitment to the natural inferiority of women in arguments for a better world, while on the left the phrase references an investment in the cultural truism, however unfounded, that we gotta work within the system we got. As a rhetorician through-and-through (although I do not throw out notions like "truth" and so forth, my moorings are constructivist to say the least), it's often difficult for me to limit my thinking to the level of MSM jockeying and take this discourse on its own terms. I firmly believe "seeing is believing," and that visual regimes participate in the hegemony of patriarchy at a pretty deep (that is, early-in-childhood) level; this is to say, I think gender is lodged at a structuring, epistemological horizon of understanding. I recognize such a view is provocative, and I'm happy to discuss that, but even so, let me briefly take up the implications of the superficial (the rhetoric of reportage) to make a larger point about presidential candidate Herman Cain's harassing proclivities, a candidate who is slowly being revealed as a straight-talker whose refreshing candor is actually buoyed by a sense of male entitlement/exceptionalism (the direct links between masculinity and an ideology of exceptionalism, of course, need not be elaborated after Bush II).

It hasn't taken long, of course, for self-identified "conservative" pundits to step forward to suggest the allegations of Cain's sexual harassment is racially motivated. Last week Ann Coulter's Cain-raising on the media circuit garnered the most attention; she suggested not only were the charges born of racism, but that Republican "blacks" are far superior to Democratic "blacks" because of the scorn they must endure to be conservatives. As the bile duct of the RepubliChristian unconscious (Marx's observation about Hegel's dialectics being upside down comes to mind), we shouldn't be surprised Coulter would say something so (ironically?) racist. Still, as Ronald Martin's CNN editorial details, pundits have been giving voice to the "race card," saying what politicians already in power cannot say. Even Cain has suggested as much himself, and after this afternoon's press conference with the forth accuser, I expect to hear more of it.

It hasn't taken long, of course, for self-identified "conservative" pundits to step forward to suggest the allegations of Cain's sexual harassment is racially motivated. Last week Ann Coulter's Cain-raising on the media circuit garnered the most attention; she suggested not only were the charges born of racism, but that Republican "blacks" are far superior to Democratic "blacks" because of the scorn they must endure to be conservatives. As the bile duct of the RepubliChristian unconscious (Marx's observation about Hegel's dialectics being upside down comes to mind), we shouldn't be surprised Coulter would say something so (ironically?) racist. Still, as Ronald Martin's CNN editorial details, pundits have been giving voice to the "race card," saying what politicians already in power cannot say. Even Cain has suggested as much himself, and after this afternoon's press conference with the forth accuser, I expect to hear more of it.

The suggestion here, of course, is that this is the black man's hour. The suggestion is that the charges of sexual harassment are a deliberate, conspiratorial distraction from the power of Cain's conservative ideas. How else do we explain the persistent polling suggesting the harassment scandals are still a non-issue among Republican supporters? Early this morning a CBS pollster noted Cain's numbers are up, and that his "testy" defiance may even help Cain's campaign. One has to wonder: so, four women claim to have been harassed sexually, to have been inappropriately treated by Cain because of their sex/gender. Four accusers is four too many, of course. Sure, there's yet to be "hard" evidence released in the media, but it's just a matter of time. And so, why is it Cain's supporters are unwilling to consider the plight of the possible victims of Cain's unwanted advances?

Although there are more insidious forms of ideological machination, at least superficially, Cain's defiance and his persistent popularity reflects how ideology actually works. Ideology is "overdetermined," as the story goes, and works in ways more akin to a complex machine of moving parts than conspiracy, making critique something like "whack a mole" when one attempts to address ideology as the multi-headed Hydra that it is: one can claim the feel-good mantle of fighting racism while propping sexism. Ideology works this way, sideways, shifting the terrain almost always in the name of The Good. And it's not just in the case of Cain, in which the rhetorical structure of the "high tech lynching" laid by the Supreme Thomas twenty years ago has been redeployed again; it's rather a persistent and deep structure rooted in the nineteenth century that argues for equality in the gestures of inequality. Among those of the Left there is a great temptation to suggest "we" are somehow exempt from the ideological machine, but how soon folks forget the presidential campaign of 2008: remember, folks, Hillary Clinton suffered a similar fate, losing a bid for the presidency because it was, yet again, the "black man's hour." As bell hooks and countless cultural critics have argued both inside and outside of the academy, one cannot fight misogyny or racism or class disparity without recognizing their deep, interlocking and mutual implication. This is why Anthony was, in the end, right to resist supporting the fifteenth amendment back in the 1870s: equality is a total horizon, not merely a sum of discrete parts clamoring for recognition.

its synth-post-punk friday!

carnEVIL 2011!

Music: Pale Saints: In Ribbons (1992)

In 2002 I started throwing an annual costume party, first at my home in Baton Rouge and now continued here in Aus-Vegas. I've always thought it was a good time for friends and colleagues to mingle (and merge); like Mardi Gras, Halloween is a holiday for collapsing hierarchies: kids get to be adults and demand treats from other adults; adults get to regress to childhood again; girls get to dress like hos; and boys, well, boys get to dress like girls. Not that any of these transformations doesn't already happen on a daily basis (just ask my colleagues how childlike I can become at any mention of a 9:00 a.m. meeting). The longer I do it and the older I get, the more I like to turn over the theme to those more younger and creative than me. And this year is proof positive this is good judgment. As a co-host, I'm really only the DJ with party favors (that is, lighting)---the real creative genius behind this year's party is Rob Mack and Ashley Mack (no relation except that, um, they are geniuses).

In 2002 I started throwing an annual costume party, first at my home in Baton Rouge and now continued here in Aus-Vegas. I've always thought it was a good time for friends and colleagues to mingle (and merge); like Mardi Gras, Halloween is a holiday for collapsing hierarchies: kids get to be adults and demand treats from other adults; adults get to regress to childhood again; girls get to dress like hos; and boys, well, boys get to dress like girls. Not that any of these transformations doesn't already happen on a daily basis (just ask my colleagues how childlike I can become at any mention of a 9:00 a.m. meeting). The longer I do it and the older I get, the more I like to turn over the theme to those more younger and creative than me. And this year is proof positive this is good judgment. As a co-host, I'm really only the DJ with party favors (that is, lighting)---the real creative genius behind this year's party is Rob Mack and Ashley Mack (no relation except that, um, they are geniuses).

This year's theme was "carnEVIL," to be interpreted however one wished. The living room/dance floor was transformed (with the aid of crafty tablecloths) into a big, red top tent! It looked amazing, and made for a fantastic dance floor once the fog machine and lights got spinning. Just beyond that was a Fun House/Hall of Mirrors animated by strobe lights (aka, the pukey-room; also see Herr Gravitron). The kitchen became a glow-in-the-dark Midway Graveyard, with lots of strangled stuffed animals hanging on nooses. There was a staging area, and a refreshments area, of course.

This year's theme was "carnEVIL," to be interpreted however one wished. The living room/dance floor was transformed (with the aid of crafty tablecloths) into a big, red top tent! It looked amazing, and made for a fantastic dance floor once the fog machine and lights got spinning. Just beyond that was a Fun House/Hall of Mirrors animated by strobe lights (aka, the pukey-room; also see Herr Gravitron). The kitchen became a glow-in-the-dark Midway Graveyard, with lots of strangled stuffed animals hanging on nooses. There was a staging area, and a refreshments area, of course.

Out in the back patio was the biggest surprise: A bouncy castle (a.k.a. the Vomitorium)! The bouncy castle was truly over-the-top and an outstanding hoot (and folks used it, I'm happy to report, without . . . "incident"; wardrobe malfunctions? Yes. Motion sickness? No.).

Out in the back patio was the biggest surprise: A bouncy castle (a.k.a. the Vomitorium)! The bouncy castle was truly over-the-top and an outstanding hoot (and folks used it, I'm happy to report, without . . . "incident"; wardrobe malfunctions? Yes. Motion sickness? No.).

Perhaps owing to the theme this year, the costumes were both amazing and incredibly creative. I liked almost all of them, but among my favorites: Maegan's super-creepy "Bloody Mary" costume, which won the award for "Scariest." Basically, she appeared as a sink and mirror, but when she turned on the light inside her witchy face greeted you (sucking on a sippy cup of booze, of course). I found Camille's ringleader costume smashing, and we looked great together!

Perhaps owing to the theme this year, the costumes were both amazing and incredibly creative. I liked almost all of them, but among my favorites: Maegan's super-creepy "Bloody Mary" costume, which won the award for "Scariest." Basically, she appeared as a sink and mirror, but when she turned on the light inside her witchy face greeted you (sucking on a sippy cup of booze, of course). I found Camille's ringleader costume smashing, and we looked great together!

The funniest costume went to the corndog-(non)chomping Bachmann duo, who temped everyone on Saturday with their corndogs---rubbing them on their faces, each others' faces, the faces of strangers. Them corndogs really got around . . . and the pair cinched (or clenched?) the "Funniest Costume" award. There's too many good costumes to mention here, so, I'll invite you to live vicariously through the photo gallery here. Suffice it to say at some point in the evening I stopped taking photographs to protect the guilty. If you were there, you know what you saw. If you weren't, well, you'll just have come next year---the tenth annual costume party bash DJ-ed by yours truly, and sadly, the last to be hosted by our creative party geniuses, Rob and Ashley. Until then . . . .

The funniest costume went to the corndog-(non)chomping Bachmann duo, who temped everyone on Saturday with their corndogs---rubbing them on their faces, each others' faces, the faces of strangers. Them corndogs really got around . . . and the pair cinched (or clenched?) the "Funniest Costume" award. There's too many good costumes to mention here, so, I'll invite you to live vicariously through the photo gallery here. Suffice it to say at some point in the evening I stopped taking photographs to protect the guilty. If you were there, you know what you saw. If you weren't, well, you'll just have come next year---the tenth annual costume party bash DJ-ed by yours truly, and sadly, the last to be hosted by our creative party geniuses, Rob and Ashley. Until then . . . .

it's hard times all around (default)

Music: Skinny Puppy: HanDover (2011)

A couple of days ago I decided to resist the magnetism of screens and attend to some repairs and removals, mostly in the garden. Many plants, thoroughly ravaged by the summer heat, had become dead things that just needed to be buried in a dumpster. Coming home after a long day at the university, I noticed on the short walk from the patio gate to the back door green things had returned. And among the green things were dead things, too far gone (long past gone and neglected). I reasoned the sight of brown and crinkled leaves was somehow crafting an unconscious graveyard mood as the days passed, a mood suitable for Halloween, of course, but not everyday. Strong winds had blown down the mirrors I had hung on the western wooden wall to create a sense of space. After I dumped half a dozen exoskeletons formerly known as flora, I set about to rehang the mirrors. Hammer in hand, I steadied myself on an acacia wood bench and lifted my arm when I soon realized---or rather, retroactively realized---that I was falling; I thrust out my harms and hands to save face. My left palm cleft, confronting a concrete jutting and I scraped the skin off of my knuckles on the right hand.

I slumped on the hard, cold patio floor and thought about it. At first there was no pain. That took a few seconds to come. And in that tiny span of time I remembered impaling a wrist on a barbed wire when I was eleven, the curly spire poking out of my palm, and then the nausea that washed over me, and then resisting the urge to throw up. But I didn't feel that same nausea, just remembered it. And then I remembered all the things I had to do before bedtime and reasoned I should simply just get up and wash up and move on.

When I have nightmares they almost always involved disappointing someone. This week: forgetting some birthdays. I dreamed a parent and then a friend were upset with me. Only after the dream did I recall I had missed the birthdays. Still, aside from letting others down, my nightmares involve bodily traumas: drowning or car accidents. Trauma, often a blunt one. Falling reminded me of these premonitions, however briefly. Not so much parting flesh; I will not die by cutting, I don't think. So: get up.

A leg on the bench had rotted and it collapsed under me. I bled---too much for the scrapes, I thought. The bench ended in the dumpster along with former geraniums. The baby blue pajamas I wore took on a brown, polka dot pattern in spots.

The garden looks better without the dead. There's always a slight sense of guilt when dumping the dead; it's as if I should leave the carcass in the garden to remind myself of the failures (gardens often appear like resumes, don't they?). The mirrors are hung, and scabs have formed on fingers and knees. Still, there's nothing quite like a simple fall to remind one of the smell of trauma---those heightened senses, that retroactive doubt about one's sense of security (or immortality, as infantile as it is). You know the feeling: the inchoate sense of dread that says, for a millisecond, "I'd rather be in bed reading a book than falling on the concrete right this moment." No one enjoys falling on concrete, even for the memories the falling might provoke.

The clutch on my car went out this week. Things, you know, fall apart.

My friend's mother, I learned at dinner, is back in the hospital. I'd say such news "comes with age," but really, it does not. I simply think such news is more in mind as we age.

A student's father was in a hit-and-run accident and she missed class. Another student reported her mother had a stroke last week, and she was busy tending to her. A friend of mine in the Midwest reported that one of his students was killed a couple of weeks ago. This is one week.

It's hard to worry about students' assignments when you find yourself saying, "don't worry about class; you need to focus on what's most important, and that's your family." What is this call for "accountability" in higher education when we are caused to consider the personal lives of students? Does accountability make exceptions for making exceptions? Is it ever alright to attend to the green things instead of the screens, and if so, can you measure that attention? The dead and dying are invisible on screens and pages.

A friend of mine teaches fifth grade. She says aside from the challenge of teaching her bilingual students to take the "no-cog-left-behind" exams, one of the most pressing problems of teaching is head lice (and getting it once a year from her students).

"Accountability" is not, it would seem, a word that is synonymous with responsibility. Response-ability: the capacity or faculty of response and recognition, and some would argue that this capacity entails an obligation to attend to the dead. Response-ability is a quality, a character trait, something that is cultivated, like a virtue. Accountability has become, more or less, a term for surveillance measured in number. Accountability has ceased to be response-able. In the world of policy, accountability my be obligatory, but that obligation is compulsory, or at least seems increasingly so.

And if I return to screens and pages, there is a toad in the garden. A poisonous toad. I read with some interest Rick Perry's "interview" in Parade this past Sunday; his smug portrait appears on the front. He believes global warming is a "fiction," among other things you might expect him to believe. He also quipped that making severe changes in the department of education (presumably modeled on the slashes he made to public services in Texas) would reduce the national deficit. He is proposing a "flat tax," that fantasy of equity that appeals, much like Ayn Rand's writing, to the firm exhilaration of negative liberties: it does not matter that your lover has smacked you across the mouth, drawing blood. Of course, it's violence, but what matters is that the blow was good for you---it even turns you on a little. Everything is in its place, like the imagined scenes of domesticity in the Pottery Barn catalog.

As Benjamin once warned, the aestheticization of the political aims at the beautification of death. We should be wary of leaders who hold out infantile fantasies of omnipotence. When death looks pretty the ugly death will come. There are no lice in the Pottery Barn. Or gurneys.

it's synth-pop friday!

what’s a regent? continued . . .

Music: Nine Inch Nails: Ghosts I-IV (2008)

Last May I reported that I didn't quite understand the role of the Board of Regents in governing the University of Texas and that I would spend the summer poking around to figure it out. I've come a little closer to getting a handle on their role, which has invited the national spotlight because of Perry's bid for the presidency and a number of high profile, political appointments in various state education agencies. The short answer is that the regents are political appointees and wield tremendous power in the UT system; they are constrained only by popular, political sentiment and legislative will. The Board of Regents has the power to hire and fire the university president, and the chancellor of the UT system also serves at their pleasure. The chancellor is the figurehead, both a policy pusher and a fundraiser---key person for the administration and corporate side of things.

My education concerning the regency mostly comes from a book recommended by Rosa Eberly, The Tower and the Dome: A Free University Versus Political Control (1971) by former UT president Homer P. Rainey, who served the University of Texas from 1939 to 1944. An outspoken defender of the tenure system and academic freedom, Rainey was fired by the Board of Regents for defending the university from politicization. Although the story is long and complicated, the trouble started when Texas governors W. Lee O'Daniel and Coke Stevenson "staked" the regency with appointees opposed to "New Deal" legislation. During Rainey's tenure, a number of the regents called on him to fire four full economics professors for teaching "radical" views. Rainey refused, citing tenure protections and the principles of a "free university," where upon a many-year struggle ensued, eventually going public. The regents began meddling in the UT curriculum and fired three untenured economics professors, leading Rainey to make charge the regents with sixteen violations that he publicized. Despite widespread popular support, Rainey was ousted. Rainey eventually moved on to the University of Colorado and had a productive career, publishing The Tower and the Dome as a principled account of the controversy (the book is full of memos, speeches, and policies).

My education concerning the regency mostly comes from a book recommended by Rosa Eberly, The Tower and the Dome: A Free University Versus Political Control (1971) by former UT president Homer P. Rainey, who served the University of Texas from 1939 to 1944. An outspoken defender of the tenure system and academic freedom, Rainey was fired by the Board of Regents for defending the university from politicization. Although the story is long and complicated, the trouble started when Texas governors W. Lee O'Daniel and Coke Stevenson "staked" the regency with appointees opposed to "New Deal" legislation. During Rainey's tenure, a number of the regents called on him to fire four full economics professors for teaching "radical" views. Rainey refused, citing tenure protections and the principles of a "free university," where upon a many-year struggle ensued, eventually going public. The regents began meddling in the UT curriculum and fired three untenured economics professors, leading Rainey to make charge the regents with sixteen violations that he publicized. Despite widespread popular support, Rainey was ousted. Rainey eventually moved on to the University of Colorado and had a productive career, publishing The Tower and the Dome as a principled account of the controversy (the book is full of memos, speeches, and policies).

Rainey explains the power structure of the regency this way:

The University of Texas is a constitutional university; that is, it was provided for by the Constitution of Texas and not by legislative statute. It is controlled by a Board of Regents of nine members. These members are appointed by the Governor and confirmed by the Senate. Appointments are made for six-year terms which are staggered in such a way that the terms of one-third, or three Regents, expire every two years. The Governor is elected for a two-year term [today it is four years]; consequently, each time a governor is inaugurated he has the privilege of appointing three regents. If a governor is elected for a second term, two-thirds of the Board will consist of his appointees, and by this process he can if he desires, secure control of the Board by appointment men committed to his policies.

As Rainey tells the story, high-level meetings were held in the late thirties by politicians to "take control" of the university system, expressly for the purpose of controlling what is taught. This resulted in "staking" the regency to push forward policy reform that comported with what has come to be known as "conservative" values (at that time, "anti-Communist" values and profound disdain for New Deal reforms).

The comparisons of the current regency to the one appointed during Rainey's time are plain; all nine regents and the student representative were appointed by Perry: Alex M. Cranberg, James D. Dannenbaum, Paul L. Foster, Printince L. Gary, Wallace L. Hall, Jr., R. Steven "Steve" Hicks, Brenda Pejovich, Wm. Eugene "Gene" Powell, John Davis Rutkauskas, and Robert L. Stillwell. Of course, Perry has been governor forever, so it makes sense he would have appointed the whole board. Nevertheless, one can easily understand why there is high tension in the current higher education environment in Texas.

That the board is awash in Perry appointees explains why there is so much controversy about higher education reforms in Texas: the governor---an office that is relatively weak compared to other states---can push through pretty drastic changes should he want to do so. This makes, of course, the university president's job an especially tricky one, taking history as our measure. This may also explain why the Chancellor has "given in," so to speak, to the demands of the Texas Public Policy Foundation's "seven breakthrough reforms" stressing higher accountability and "more" productivity. The agenda has been set: increase enrollment, decrease tuition, teach "blended" classes (which is to say, adopt the University of Phoenix model), and stop supporting "frivolous" scholarship. Scholarship like mine, of course, which takes popular culture as a serious academic subject.

it's synth-pop friday!

occupancy

Music: HTRK: Marry Me Tonight (2008)

Witnessing the worldwide ruckus now widely reported as the Occupy Movement, surely I am not the only one who has been thinking of R.E.M.’s song, “Welcome to the Occupation,” from 1987s Document (if you don’t know the song, I recommend a listen). Back in the late 80s, I always thought the song was about the dispiriting discipline of the "office collar" job, beating the "teen spirit" out of ya: "You are mad and educated/primitive and wild/ welcome to the occupation." Back then, I enjoyed my afterschool job working at Little Caesar's Pizza. It didn't pay very well, but the owner was kind (he often worked along side us and just as hard) and there was a fun camaraderie among the folks who worked there. No hierarchy, very little at stake, and minimal politics. We made pizzas. They were cheap. People got happy.

Witnessing the worldwide ruckus now widely reported as the Occupy Movement, surely I am not the only one who has been thinking of R.E.M.’s song, “Welcome to the Occupation,” from 1987s Document (if you don’t know the song, I recommend a listen). Back in the late 80s, I always thought the song was about the dispiriting discipline of the "office collar" job, beating the "teen spirit" out of ya: "You are mad and educated/primitive and wild/ welcome to the occupation." Back then, I enjoyed my afterschool job working at Little Caesar's Pizza. It didn't pay very well, but the owner was kind (he often worked along side us and just as hard) and there was a fun camaraderie among the folks who worked there. No hierarchy, very little at stake, and minimal politics. We made pizzas. They were cheap. People got happy.

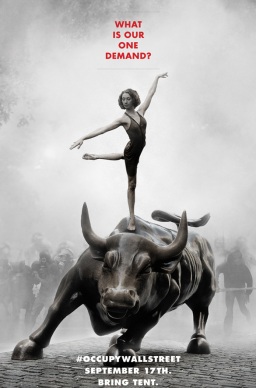

Watching the protests in New York spread across the globe this last week, it seems the movement has finally achieved traction in the mainstream news media. As Kevin DeLuca argued in his book Image Politics over a decade ago, social movements have been drifting toward a kind of postmodern politics of representation, harnessing the power of mediated circulation as a or the means of mobilizing affect. Although I've always had some trouble with DeLuca's argumentative particulars, I think he captured the emergence of a new form of global political organization; his and Peeple's subsequent notion of the "public screen" certainly seems apropos in this moment, especially when we take up the oft-heard question, "but, what do they want?" What is, in other words, the signified that would anchor all this unrest into a series of demands? (Notably, one of the original posters for the Occupy Wall Street protest deliberately leaves the questions unanswered).

Comparisons to the Tea Party movement have been common---or rather, have been often denied, which is the acknowledgement of a comparison. This had led me to think about what, exactly, the basis of any comparison might be. Aside from the obvious role of information technology and the "swarming" mobilizations this has enabled, we might say both lack a clearly identified leader. Protests to the contrary from the Tea Partiers—or rather, just a few fiery ones who are "friends" on a social networking site—both also lack a clear set of demands. I don't consider calls for "smaller government" or an end to corporate greed a demand. Prima facie, it would seem that the bedrock commonality is a brand of political nihilism in which the movement is defined against an established or projected order of one sort or another (for one, the illusion of liberal conspiracy; the other, the reality of global capital).

I'm still thinking. But, like a treasure hidden in plain sight, I do find it surprising that few commentators and critics are talking or writing about the concept that has helped to organize so many: occupancy. The original call to "occupy Wall Street" signified, on a basic level, putting bodies in a certain space as a metaphorical squatting ("bring tent," the original flyer says). The term also has militaristic connotations of property seizure and violation of ownership. Even the term "occupation," now metonymy for one's profession or even class-identification, derives from a person located in a particular space. Unlike the Tea Party movement, which seemed to organize an inchoate swirl of rage, xenophobia, and classic "American" paranoia, the Occupy Movement started as a political gesture of space. This marks it as something more---or perhaps something other than---a politics of spectacle.

Occupancy harkens to street marching politics of old in a way that flies in the face of theories of digital mobilization or virtuality. What the Occupy Movement seems to be harnessing, however paradoxically, is a strange, postmodern politics of invisibility made possible by postmodern regimes of publicity. What I mean by this harkens to Hakim Bey's conception of the Temporary Autonomous Zone, in a sense: insurrection occurs in spaces that have gone "unmapped" by the state. Or to use Henri Lefebvre's notions of representation, the Occupy Movement seems to be pointing up the distinction between "representations of space" (which serve the dominant class) and "spaces of representation," the latter concerning how people actually occupy the world with their bodies, often in ways that do not comport with dominant conceptions of space. The territory of lived lives---the structures of feeling and being in the world---exceeds what is capable of being represented.

For example, consider how long it took the MSM to get around to representing the Occupy Wall Street protest: it took almost two weeks for screen-time to reflect what New York citizens were experiencing in Manhattan. This "lag" time in "mapping" the movement represents in a homologous way the "lag" between representations of the experiences of "everyday folks" and what is perceived as consensus-reality on our many screens. My point is that Tea Party mobilization was conducted largely on the terrain of virtuality (despite some modest rallies and a Fox-News sponsored DC thing), whereas it appears that the Occupy Movement is manifesting quite differently---adding a spatial component to the temporally bound logics of publicity and circulation. In other words, occupancy is the central tactic, and the image politics of the tactic is secondary. Of course, this was the strategy of uprisings in the Middle East, presumably in countries with less sophisticated technologies of mediation and representation; clearly, however, a number of those involved in the Occupy Movement believe the spatial tactic is crucial. Those who study social movements in postmodernity would do well not to lose sight of occupancy as a strategy.

Evidence enough that the Occupy Movement is engaging in a territory map struggle are the attempts of those "on the right" who would force it into a state-sanctioned map. Consider, for example, George Will's conclusion in a recent column:

As Mark Twain said, difference of opinion is what makes a horse race. It is also what makes elections necessary and entertaining. So: OWS vs. the Tea Party. Republicans generally support the latter. Do Democrats generally support the former? Let’s find out. Let’s vote.

Isn't the reduction of social struggle to the ballot precisely the mechanism occupancy seeks to combat? Martin Luther King comes to mind . . . .

it's synth-pop friday!

halloween pr for the aus-vegas mothership

Music: Jesca Hoop: Snowglobe EP (2011)

Because of my “expert profile” on the media relations pages of my employer, about the second week of October I start getting requests for interviews about all thing that go bump in the night. I’ve done a lot of interviews on the topic of Halloween and ghosts (this year some show called Ancient Aliens called, but they seemed to want me to say some things that I would never say). Often journalists ask the same questions, and it’s difficult not to use the same answers, since they’ve almost become memorized scripts. It’s an odd thing.

Because of my “expert profile” on the media relations pages of my employer, about the second week of October I start getting requests for interviews about all thing that go bump in the night. I’ve done a lot of interviews on the topic of Halloween and ghosts (this year some show called Ancient Aliens called, but they seemed to want me to say some things that I would never say). Often journalists ask the same questions, and it’s difficult not to use the same answers, since they’ve almost become memorized scripts. It’s an odd thing.

A slightly higher profile interview will be going out on ProfNet’s Newswire subscription service, which alerts journalists to experts on everything from sniffing underarms to bunny sniffs. Maria Perez of ProfNet interviewed me over the weekend, and I’ve been asking if I could write my answers lately (so I can check the language; memory is choosey when speech is involved). Because this is taking up the last two hours of the week I try to reserve for blogging, I asked her if I could post our interview here. She said agreed, as long as I provide a link to the actual story. That won’t be out for a couple of weeks, and I’ll provide that here as soon as it is official on the Intertubes. Meanwhile, here is a preview:

What led you to teaching about this topic?