occupancy

Music: HTRK: Marry Me Tonight (2008)

Witnessing the worldwide ruckus now widely reported as the Occupy Movement, surely I am not the only one who has been thinking of R.E.M.’s song, “Welcome to the Occupation,” from 1987s Document (if you don’t know the song, I recommend a listen). Back in the late 80s, I always thought the song was about the dispiriting discipline of the "office collar" job, beating the "teen spirit" out of ya: "You are mad and educated/primitive and wild/ welcome to the occupation." Back then, I enjoyed my afterschool job working at Little Caesar's Pizza. It didn't pay very well, but the owner was kind (he often worked along side us and just as hard) and there was a fun camaraderie among the folks who worked there. No hierarchy, very little at stake, and minimal politics. We made pizzas. They were cheap. People got happy.

Witnessing the worldwide ruckus now widely reported as the Occupy Movement, surely I am not the only one who has been thinking of R.E.M.’s song, “Welcome to the Occupation,” from 1987s Document (if you don’t know the song, I recommend a listen). Back in the late 80s, I always thought the song was about the dispiriting discipline of the "office collar" job, beating the "teen spirit" out of ya: "You are mad and educated/primitive and wild/ welcome to the occupation." Back then, I enjoyed my afterschool job working at Little Caesar's Pizza. It didn't pay very well, but the owner was kind (he often worked along side us and just as hard) and there was a fun camaraderie among the folks who worked there. No hierarchy, very little at stake, and minimal politics. We made pizzas. They were cheap. People got happy.

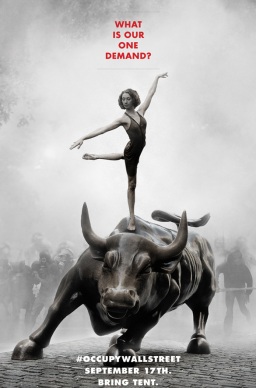

Watching the protests in New York spread across the globe this last week, it seems the movement has finally achieved traction in the mainstream news media. As Kevin DeLuca argued in his book Image Politics over a decade ago, social movements have been drifting toward a kind of postmodern politics of representation, harnessing the power of mediated circulation as a or the means of mobilizing affect. Although I've always had some trouble with DeLuca's argumentative particulars, I think he captured the emergence of a new form of global political organization; his and Peeple's subsequent notion of the "public screen" certainly seems apropos in this moment, especially when we take up the oft-heard question, "but, what do they want?" What is, in other words, the signified that would anchor all this unrest into a series of demands? (Notably, one of the original posters for the Occupy Wall Street protest deliberately leaves the questions unanswered).

Comparisons to the Tea Party movement have been common---or rather, have been often denied, which is the acknowledgement of a comparison. This had led me to think about what, exactly, the basis of any comparison might be. Aside from the obvious role of information technology and the "swarming" mobilizations this has enabled, we might say both lack a clearly identified leader. Protests to the contrary from the Tea Partiers—or rather, just a few fiery ones who are "friends" on a social networking site—both also lack a clear set of demands. I don't consider calls for "smaller government" or an end to corporate greed a demand. Prima facie, it would seem that the bedrock commonality is a brand of political nihilism in which the movement is defined against an established or projected order of one sort or another (for one, the illusion of liberal conspiracy; the other, the reality of global capital).

I'm still thinking. But, like a treasure hidden in plain sight, I do find it surprising that few commentators and critics are talking or writing about the concept that has helped to organize so many: occupancy. The original call to "occupy Wall Street" signified, on a basic level, putting bodies in a certain space as a metaphorical squatting ("bring tent," the original flyer says). The term also has militaristic connotations of property seizure and violation of ownership. Even the term "occupation," now metonymy for one's profession or even class-identification, derives from a person located in a particular space. Unlike the Tea Party movement, which seemed to organize an inchoate swirl of rage, xenophobia, and classic "American" paranoia, the Occupy Movement started as a political gesture of space. This marks it as something more---or perhaps something other than---a politics of spectacle.

Occupancy harkens to street marching politics of old in a way that flies in the face of theories of digital mobilization or virtuality. What the Occupy Movement seems to be harnessing, however paradoxically, is a strange, postmodern politics of invisibility made possible by postmodern regimes of publicity. What I mean by this harkens to Hakim Bey's conception of the Temporary Autonomous Zone, in a sense: insurrection occurs in spaces that have gone "unmapped" by the state. Or to use Henri Lefebvre's notions of representation, the Occupy Movement seems to be pointing up the distinction between "representations of space" (which serve the dominant class) and "spaces of representation," the latter concerning how people actually occupy the world with their bodies, often in ways that do not comport with dominant conceptions of space. The territory of lived lives---the structures of feeling and being in the world---exceeds what is capable of being represented.

For example, consider how long it took the MSM to get around to representing the Occupy Wall Street protest: it took almost two weeks for screen-time to reflect what New York citizens were experiencing in Manhattan. This "lag" time in "mapping" the movement represents in a homologous way the "lag" between representations of the experiences of "everyday folks" and what is perceived as consensus-reality on our many screens. My point is that Tea Party mobilization was conducted largely on the terrain of virtuality (despite some modest rallies and a Fox-News sponsored DC thing), whereas it appears that the Occupy Movement is manifesting quite differently---adding a spatial component to the temporally bound logics of publicity and circulation. In other words, occupancy is the central tactic, and the image politics of the tactic is secondary. Of course, this was the strategy of uprisings in the Middle East, presumably in countries with less sophisticated technologies of mediation and representation; clearly, however, a number of those involved in the Occupy Movement believe the spatial tactic is crucial. Those who study social movements in postmodernity would do well not to lose sight of occupancy as a strategy.

Evidence enough that the Occupy Movement is engaging in a territory map struggle are the attempts of those "on the right" who would force it into a state-sanctioned map. Consider, for example, George Will's conclusion in a recent column:

As Mark Twain said, difference of opinion is what makes a horse race. It is also what makes elections necessary and entertaining. So: OWS vs. the Tea Party. Republicans generally support the latter. Do Democrats generally support the former? Let’s find out. Let’s vote.

Isn't the reduction of social struggle to the ballot precisely the mechanism occupancy seeks to combat? Martin Luther King comes to mind . . . .