terms of endearment

Music: Rolling Stones: Some Girls (1978)

I was saying goodbye to a friend, a former teaching assistant and a current graduate student, some years my senior, in most ways wiser and with knocks harder than I can imagine. Second career. She was putting on a helmet and mounting a scooter. “Thanks Josh,” she said, referencing our working lunch meeting. “Thank you for lunch, darlin’” I said, almost automatically. I noticed, in that split second, the “darlin’” was unwittingly testing a boundary. She registered, made eye contact, then cracked a smile. “You bet, babe.” And off she scooted.

Unspoken negotiation happens daily, in gesture and mood; words spoken only index a torrent of scripts churning out behind observing eyes. That is, the speakers who are seasoned at self-monitoring scan the scripts, quickly.

I think culture shock has its advantages. I was born and raised in Georgia. Lived in DC. Moved to the Midwest. Moved to Louisiana. Then moved to Texas. Shocking every year of the way.

It’s taken me a long time, but I have finally come back around to occupying a speech orientation, a sort of idiomatic disposition, that I was reared into as a son of Georgia: relating to others with terms of endearment. Growing up, I was called “dear,” “sweetie,” “darlin’,” and all matter of cute names that are so stereotypical of being a kid from the south. When I moved away from “Dixie,” it was initially difficult adjusting to being addressed a “sir” or “mister” at the grocery store. But I acclimated, eventually. When I moved to Minnesota in my early twenties, I learned that referring to others as “sweetie” and “darlin’” could be taken as an insult. And much of the reason concerned gender relations.

Graduate school, a deepening (and I think fairly extensive) education in the history of misogyny and sexism, and a certain midwestern sense of propriety oriented my whole being toward a certain comportment, a concern with the respect and dignity of others. In Minnesota, if I wanted to call a friend by “sweetie” or “dear,” I knew that it might be heard as an assertion of superiority or patriarchical right---so I simply stopped referring to people in that language. Over the course of six years, my body acquiesced. Calling others by the southern terms of endearment simply left my vocabulary; “dude” entered my vocabulary as a sort-of substitute (for men and women with whom I was close; I think my Dixie-diction just got Cali-clobbered---in Minnesota!).

What I learned in graduate school is that calling others “sweetheart” or “darlin’” was at some level an assertion of power, drawing on a logic that stretched back decades, perhaps centuries. What seems like an innocent admission of affection is really an assertion, for example, of male superiority over women, or an assertion of male privilege, or a tacit reminder of my (assumed) power, or so on. We’re all familiar with the arguments (well, most of the folks who read this blog, anyway). What I’m trying to write about is how irresistible those habits are, how throwing out those terms of endearment are so soul-deep, so unconscious, how the gestures are learned so early that they are as much a form of dancing as they are a perpetuation of a kind of ideological perseveration (think Lacan on the agency of the letter, here).

For example: there’s another thing that I was taught as a young person that I simply cannot seem to shake: holding doors open for others behind me who are elderly or women (we’ll, frankly, I do this for just about everyone). I was taught at a very young age---before I can consciously remember---to do this. And I was taught to make sure the elderly and women exit elevators before I do. I’ve tried to break this habit, but I can’t. I still do it. Unfailingly. I can recall thinking just last week: I was standing at the front of a crowded elevator car going up to the seventh floor, and a number of young, female students were behind me, and I thought that I should let them exit before I do. I recall thinking also that maybe I should just walk out of the elevator first, because waiting represented a certain male superiority. But when the door opened, I used my arm to hold open the door and let the women out before I got out. Force of habit. Force of entrainment.

Is the force of habit also the force of hegemony? Probably.

But I also think, increasingly, the force of habit is alright, that my graduate school self is being too hard on my middle-aged self reverting to adolescent habit.

As my opening anecdote reveals, I’ve started letting myself use terms of endearment for people. No doubt that’s because I live in a state for which this is common and expected; clerks at the grocery store call me “darlin’” (usually women), and I like it. My closest friends do it (Dale calls me “babe,” Mirko calls me “buddy,” Shaun tells me “I love you, bud” at the end of every phone call, Diane calls me “sweetie”). But I’m trying to be mindful about it. I want the folks whom I call “sweetie” or “darlin’” to know that my terms of endearment are deployed carefully, with the full knowledge that there’s a complicated power structure I’m navigating when address them so, that I’m aware of this structure, and that I do it anyway. I guess what I’m trying to say is that if I call you “sweetie,” you should know that I’m not necessarily on some hegemonic autopilot, or asserting some sort of power relation, but rather that I love you.

But is it the hegemonic speaking through me? Perhaps. At some level. I guess at this point I’m willing to take the risk, darlin’. And that I think the nature of the risk is more endearing than oppressive.

This is the sort of “over-thinking” that academics are made-fun of for, that my own family teases me about. Still, it’s an interesting, everyday gesture that bespeaks an intellectual journey few of those who have not had an education in feminism and gender studies think about. But if I call you “darlin’,” rest assured I have thought about the implications (I think?). And, I hope, you realize I’ve taken risk---the risk that I know all that and still want to risk it, that you are my equal, and that you are truly dear to me.

But: This is why I only will use such terms of endearment with those who are dear to me and know me---because I suppose that they know where it’s coming from. And at some level I think I assume those for whom I use such terms of endearment would tell me that they find it offensive if they actually find it offensive. In which case, I guess, I would just call them “dude”---regardless of gender, or, well, religious conviction.

it's synth-pop friday!

five things I dislike about shopping at central market

Music: Tori Amos: Night of Hunters (2011)

My favorite grocery store in Aus-Vegas is Central Market, a less-expensive port of Whole Foods, and less pretentious too. They also carry lobster, which Whole Foods refuses to do because they believe boiling crustaceans causes sentient pain. Central Market is a little more expensive than the average grocery store, and a lot more expensive than Wal-Mart. But, they have good employee relations (and benefits), and in general the customer service is really great (the same is true of Whole Foods). Still, as Eeyore is my patron saint, I managed to find some things worthy of complaint, most of which have to do with the people who shop there:

1. The lady who steps out in front of my car when I am trying to park: I’m about to turn into a space when a sunglassed young woman looks up, sees me coming, and decides nevertheless to walk in front of me, causing me to slam on my brakes. But instead of scuttling to get out of the way, she elects to “text” on her phone in this jaywalkish moment, slowing her pace substantially. She cost me an extra ten seconds. Lady: you deserve to get hit the next time you do that.

2. The older woman dressed in all black who cuts in front of me to price her produce: I’m walking toward the scale one has to use the produce department to print off a price label, based on the weight of your produce. I’m about three feet away when a blond woman plops in front of me to weigh her produce. This is fine, she didn’t see me. As I stand behind her waiting patiently, another woman, elderly and dressed in all black, approaches the opposite side of the woman weighing and looks at me. Then, when the first woman is done the lady dressed in black plops down a big ol’ bag of green peppers. She doesn’t say “sorry” or “excuse me.” Just because you are older than me doesn’t mean you don’t need to observe common courtesy. Grrr.

3. The cheese sample hogs: So, one of the rare delights of shopping at Central Market is that they are always doling out food samples. The best are always in the cheese department. There’s a bar, and on it sits a sample tray, and as a matter of sequence, when shopping at Central Market, one always has to make a pass through the cheese section for that free sample. Today two women were sampling as I neared. I went off to another section to fetch something, and then came back. They were still sampling. They kept sampling. Like I watched them take three samples each. You know, I think you’re only supposed to take one sample, people. Then move and let others sample. Grrr.

4. The lack of pork rinds: Almost every grocery store in town sells pork rinds. Pork rinds are eaten by Texans. So is salsa. Central Market has a whole aisle just for salsa and tortilla chips. Seriously. Whole Foods doesn’t have pork rinds, I reckon, because these are presumably unhealthy (no more unhealthy as the marbled meat they sell, or the margarine, and so on). But Central Market: why can’t you have pork rinds? Some recipes call for crumbled pork rinds for texture. I dislike that you do not have pork rinds, Central Market, as I suspect it is really about "class." Only lower-income people eat pork rinds, and you presume you are above this, Central Market? Boo.

5. The jock who has an intense conversation with girlfriend on his cell phone while checking-out: Dude, neither me, nor the clerk, care about your relationship troubles, and your public airing of them significantly slows down the process. It’s difficult to swipe your card and punch your PIN when Ginger is accusing you of insensitivity. She’s right, you know.

it's synth-pop friday!

anniversarial ramble

Music: Wilco: The Whole Love (2011)

When one gets to the dissertation stage in graduate school, life becomes gradually, almost imperceptibly, solitary. About half-way into writing hundreds of pages one looks up to see the days stretching behind her in a monotonous---even comforting---routine: get up and make coffee; review the pages written yesterday in front of the morning shoes news; read something to jump-start thinking; be at the computer by 10:00 a.m.; break for brunch; back to the computer screen; stop writing; print; proofread; make dinner or get out to see a friend. Rinse. Repeat.

At some point in the process you realize you are alone, that writing really cannot go any other way; you have to push through, and be perspicacious enough (namely, about your own tendencies) to schedule social things so that your absorption in your writing does not become totalizing. The absorption of mania, in whatever form, is often productive; the cost, however, is a certain withdrawal from the world.

September 11, 2001 was a routine day like any other. Since high school I had watched the Today show, drinking coffee as I readied for school. Dissertating mandated a regression to the same morning ritual of my younger youth, since there was comfort in routine. Tuesday. The nondescript day, a purgatory of the week’s punctuation in which something must get done, because the excuse of Friday fun was three days away. The cats were perched on the radiator, as usual, and it had already turned a chill in Minnesota. A black-and-white throw blanket my grandmother made me for Christmas was draped across my lap. She was inspired, I think, by my kitchen curtains, which she saw a picture of once and remarked that she liked (I said one day I would have a kitchen with a black and white checkered floor). I was grazing through Richard Kearney’s The Wake of Imagination to get the brain working, take notes with a red Pilot pen and an eight-inch, clear plastic ruler. The whirr and buzz of television news faded into and out of consciousness as Kearney traced the passage of the imagination from creation to reflection; Katie Couric and Matt Lauer coupled me to hard news at the top of each hour for ten minutes. Sip. Coffee. Sip. Kearney. Sip. Sip. Refill.

“. . . and I’m cold for my father/ frozen underground/ jesus, I wouldn’t bother / he belongs to me now . . . .”

Televisual occupancy is an odd thing, the charge of what Raymond Williams called “flow” carries the sound of other bodies breathing through small speakers on each side into your space, as if to convince one’s brain, at some level, you are with others while working alone. A coffee shop in your living room. A book in your lap. Two pets addicted to the radiator. Sip. Coffee. Sip. Kearney. “And it appears, we’re getting reports that, a small plane has mistakenly flown into one of the towers of the World Trade Center.”

What? Coffee. Sip. No one seemed alarmed, just confused. The speculation from Lauer was that it was a hobby plane, eyes fooled by the ground-level perspective of something so high. Live footage. Smoke trickles, then billows, out of the building. All cameras were pointed to the World Trade Center, and so when the second plane hit, many of us watching television saw it. At least, I remember seeing it, though memory is choosey (eating watermelon in the alley, she recalled discarding the husk). Memory is choosey and perhaps it’s just as likely I remembered seeing it because of the instant replays played relentlessly over the next week. Coffee. Sip. Kearney could wait.

The phone rang. It was my friend David Beard. “Are you watching television?” he asked. I was, I said. David and I had an essay in review about the shift of television news toward “real time” coverage, in 2001 still then yet a novelty. Around-the-clock coverage of unfolding events was expensive and not as routine as it is today. Our essay located the push toward “real time” coverage with the Columbine High School Massacre in 1999, when all the major television networks interrupted regular programming to cover the event. Drawing on the theories of Paul Virilio, we argued this kind of coverage would become routine (we were right, two graduate students whom few wanted to listen to, but we were right). We tried to think through how real-time could be economically viable for media corporations, since it flies in the face of the then dominant business model of selling advertising tied to programming. We argued the economic advantage was in engendering melancholia, a suspended state of wonder and horror that amplifies a sense of lack in the spectator. That heightened sense of lack could then, of course, be used to encourage consumption. Columbine. Real time. The sense of need engendered by trauma.

“Our essay is going to get published now,” I remember saying (it was, see “On the Apocalyptic Columbine”). But we didn’t just talk about how validating the news-coverage was to our “theory.” We also just talked about our feelings, what was going on, what it meant. I don’t remember how long our conversation lasted, I just remember long pauses on the phone as we watched our televisions.

The towers collapsed.

Writing the dissertation was a solitary feat. But as a witness to televised terror, I was not alone. David was on the phone. I will never forget that moment, with one of my best friends’ voice, seeing something apparently unreal made realer and realer as the day progressed. The telephone figures prominently in my memories of that day, ten years ago.

As days became weeks, months, and years, I became particularly interested in how Nine-eleven evolved into a node in the popular imaginary, how various discourses mobilized popular affect and political policy around a shared sense of trauma. My research trajectory changed, decidedly, toward understanding the relationship between human affect and the political, broadly construed. Looking over my scholarly production this past decade, I can see how influential Nine-eleven has been to my thinking: from Bush II’s orchestration of a decade-long death machine, to the “death-match” politics of contemporary statecraft (the Tea Party would not have been possible without the permissibility of public righteousness rooted in collective trauma). One thing I noticed about the media coverage of Nine-eleven was the repeated use of recorded voices, panicked phone calls to emergency personnel, especially. On behalf of the “families of victims,” The New York Times fought the city government to publically release the phone calls of victims trapped in the towers (they eventually won), and this because, the paper argued, the families needed to hear the recorded voices of their loved ones to properly mourn. Each anniversary, the memorial ceremony has featured the “reading of names”---almost 3,000 of them. In other words, it was the collective mourning responses to Nine-eleven that pushed me toward my present interest in human speech as an object, as a privileged point of focus, as this strange meeting place of language and the body, the spot where feeling gives way to meaning. I’m writing a book about it.

Today on the tenth anniversary I have been listening to NPR all day. I’ve been listening to people telling stories, relaying memories, of recalling that day and what it was like. When I woke and turned on the radio this morning, I was treated to the sound of our president reading a Pslam, which for some irrational reason angered me instantly. I’ve been thinking through this anger today: why did I get so aroused?

In part, I think I got angry because of the collapse of mourning Nine-eleven into politics (as if, of course, the two can be kept pure). So much awfulness was introduced into our lives as a result of a trauma-envy made possible by that day: a war waged via deception, another waged (however justly) as a result of that deception, airport security theatre, thousands dead to avenge the dead. And for what? A a parade of illusions, a collection of abstractions and resolute projections. The critique here, of course, has been “done to death,” too.

My friend Rosa wrote something poignant today: “don't let all the remembering, no matter how important it is---and it is important---seduce you into forgetting to remember how to think.” How soon we forget that Nine-eleven marked a new battle in the so-called culture wars. Higher education was accused, almost immediately, of brainwashing students in “liberalism” and the move was on to silence critique or the frequent (and true) suggestion that U.S. foreign relations and policy was in some sense responsible for the attack. I vividly recall a “teach-in” in which John Mowitt, a graduate teacher I very much admired, led a discussion about the new attacks on the academy. It’s a long argument to make (and I’m too tired to unfurl it here), but, much of the assault on higher education today coming from the Right is drawing on the collective trauma of that day to bully-up “reforms” and “accountability measures.” I recognize such a statement sounds a bit conspiratorial in the key of Michael Moore, but I do think there is some truth to it. Challenges to the academy are presently made in the name of recession, but Nine-eleven lurks there in the heart, because the teaching of critical thinking has more common cause with “the terrorists” than our mandate as educators. To be critical of the status quo is to be “against America.” Of course. Coffee. Sip.

I was in a rented living room sipping coffee and preparing to write my dissertation when the attacks on Nine-eleven happened. My friend phoned to share a sense of shock. It’s no mystery, then, that Nine-eleven is yoked to academic pursuit in my head. Nine-eleven represents, to me, why the personal and the professional cannot be separated; motive doesn’t discriminate its outlets. And this is why, I reckon, I smell the political machinations underneath apparently earnest attempts to mourn and memorialize, that I sense grief is being used towards murderous ends. The ritual of memorialization too easily lends itself to mass catastrophe precisely because there is nothing inauthentic about the experience and rememory of pain.

I recoil with disgust from the thought that my sense of togetherness in shared trauma, the human community made real by a shared shock, can be swerved so easily into a blind acquisition. But this is what Nine-eleven has become: an affective invocation toward the non-critical acceptance of reactive evil. I’m heartened by the recollections and stories of people who witnessed, first hand, the massive catastrophe of these attacks. I just resent someone using that heartening toward killing other people “in the name of.” This has been a strange, ambivalent day. How to feel community while resisting a mobilization to war? How to be one without excluding the Other? Without using the Other to orchestrate a heartening toward the Same?

Big questions. Perhaps pretentious, at least on some level (so why blog about it at all, right?).

These are the kind of big questions I started asking myself as a teenager. In my AP English class my senior year in high school I opted to read Jean-Paul Sartre’s novel Nausea for a final report. I was taken by the character of the “Self-Taught Man,” a person whom the protagonist meets, a smart fellow who spends his days in the library. The Self-Taught man confesses a principled love of humanity, but this love is abstract. Through this figure, of course, Sartre critiques the figure of the fascist. Roquentin challenges the Self-Taught Man or “Autodidact” to name a specific person for whom he has love, and he cannot. His love is abstract, and in that abstraction the Self-Taught Man can excuse atrocity (it is implied) toward the greater good. The reading of names in Nine-eleven memorials is an attempt to prevent this sort of abstraction. As is the day-long story-telling on NPR. How to keep this level of specificity? How to locate the affective tie without grouping feeling into some higher level of a love of country and the wars it wages on congeries of particular lives who sip coffee and talk on the phone and have dinners with friends who want nothing more than to get by and raise their children?

Why is peace an impossible thing between creatures who have the capacity to feel each other’s pain? That’s a naïve question, I know. But on this ambivalent anniversary, I never want to lose the childish bewilderment that motivates the question. “Why?” I would ask my parents. “Because I said so” was too often the answer. “Because I said so” is the problem of humanity, too often voiced as “because God says so.” And after Nine-eleven we have to ask, who is God, anyway? Abstract nouns are deadly.

it's WTF friday!

Aw, boys and girls: All Leather does it again. NSFW, or perhaps sobriety:

perryprecious on the precipice

Music: The Horrors: Primary Colours (2009)

While Aus-Vegas braces itself at the center of a ring of (wild) fire, Gov. Good Hair is prepping for his appearance tomorrow evening in the republican showcase. Fifty fires sprung up around metro Austin just in time for Perry to play the good governor managing a crisis (and, frankly, he's doing a good job here, saying what needs to be said), as if to deliver a savior on a wave of goodwill---water, you see, is in short supply---into the arms of a party divided. Polls have Perry way ahead of the Romster, and a good performance Wednesday night may just seal the deal.

While Aus-Vegas braces itself at the center of a ring of (wild) fire, Gov. Good Hair is prepping for his appearance tomorrow evening in the republican showcase. Fifty fires sprung up around metro Austin just in time for Perry to play the good governor managing a crisis (and, frankly, he's doing a good job here, saying what needs to be said), as if to deliver a savior on a wave of goodwill---water, you see, is in short supply---into the arms of a party divided. Polls have Perry way ahead of the Romster, and a good performance Wednesday night may just seal the deal.

The joke around these parts is that Perry is "like George W. Bush, but without the brains." On the surface the joke is fairly funny, given that many regarded Bush as a not-so-bright guy. The fact is, however, that Bush is a bright guy, on average as smart as most presidents (from standardized test and IQ scores released in the press, to the way he ran his campaigns and fared in presidential debates, and so on). I think the attribution of stupidity to Bush had more to do with his stubbornness and his speech (he has a pronunciation problem, if ya didn't notice). As Politico posed, the question of the moment is really this: Is Perry dumb?

The conclusion of most political journalists---especially those embedded in Texas---is a resounding "no," when we agree there are many types of intelligence. Perry is not a wonk, is not a details guy, and in general only knows what he needs to know. What story after story here in the local papers detail is Perry's profound political savvy: he's not book smart, but he's smart enough to surround himself with advisors who are, and then to do and say exactly what they tell him—sort of (it's that "sort of" that is interesting). Of course, Cheney would have us believe with his recent tell-all this is what Bush II was as well (and he was the puppet master), but I don't quite believe it. Call it nostalgia for Bush if you want, but, Perry is the real deal, the automaton of an affective resolve with shots crafted and talking points molded by a team of talented ideologues. The thing is, what folks find so convincing about Perry---attitude, bravado, seemingly off the cuff zingers---is also the "tragic flaw" that, I hope, will impede his momentum.

As many have observed, Perry is not big on debates and unscripted, ad-libbing sessions. He's not terribly good on his feet; he's good if he has a script, but pushed on an issue unprepared, he suffers from Porky Pig syndrome. For example, check out his response to local Lefty journalist Evan Smith when pushed on the program of abstinence for so-called "sex education":

Now, to be fair, abstaining from sexual intercourse does, in fact, prevent pregnancy. I'll grant the governor that. But faced with the fact we're third in the nation for unwanted pregnancies among youth, he struggles here with a good, reasoned response to Smith's questions other than an affective display of conviction.

Given the republican "debates" I have seen thus far, I'm not so sure there will be such pointed questions to Perry and the other candidates. And what troubles me is that it would seem for a good many potential voters, affective displays of conviction may be all they need. This election may come down to voting as a form of grunting.

Many years ago, deep into a fascination with Huey Long and demagoguery, I wrote many (unpublished) pages about a robot of the former governor in Louisiana's Old State Capitol building. I was trying to think-through why state officials would want a robot of Long saying folksy things to visitors and concluded it played into a strange "death wish" at the center of Louisiana culture. It's hard to explain unless you've spent any time in that state. I came up with a concept I termed the "political uncanny," the idea that the politician was, in fact, an automaton parroting this or that rhetoric for power, that the government was a grandiose machine that ran itself. The illusion of the political is that people were calling the shots, when really, if you are down with Foucault's understanding of governmentality, people are more or less articulations of the machine (that is, even politicians misunderstand power). This underlying fantasy of the political that emerges in the modern era finds expression in the animatronic politician, first pioneered by Walt Disney World (which featured robotic presidents in the 60s) and then in cinema with The Manchurian Candidate. Animatronic presidents are not hard to come by; we have one of LBJ here at UT in the presidential library that registers a "ten" on the creepy-meter (he only tells jokes).

It's not a fully developed idea, but I think with Rick Perry we have a serious manifestation of the political uncanny. While I would not evacuate the man of his humanity, he does nevertheless parrot more than he pops off an original thought---and this is precisely the "sort of" I find interesting. When Perry makes his most egregious gaffs, such as calling Bernanke "treasonous," that's not calculated; he's giving voice to something moving through him, almost as if he's possessed with a kind of prophetic voice, as if he cannot help himself. Conviction guides him, but what comes out of his mouth is often inspired. And this is the thing about the political uncanny, as I am thinking of it: its appeal is subtly nihilistic. It's dark. The appeal of Perry concerns both the "on message" dedication and the flights off the script that are something like a strong stare into the abyss. The risk-taking absurdities, of accusing a respected government official of treason, of seceding from the Union, of staying the course like Nemo, into the heart of Cthulu.

Obama has been a disappointment, and probably for reasons most of us cannot possibly fathom. But one thing Obama has not been is robotic. That he disappoints us probably should give us pause; it means he's thinking. Perhaps not in a way we would wish. He's thrown just about everyone left of center "under the bus" at this point and almost entirely alienated his base. It's not looking good. But I know Obama is not a nihilist, and I'm going to vote for him again, because I worry about the alternative (robotics).

Perry is polling well because he is riding anger. That is his appeal, and its seat is nihilism, and he'll parrot whatever he is advised to as long as it gives focus to anger. And what really, really makes me fearful is the things he's choosing to target.

For the debates on Wednesday, I'm going to be listening for questions about two things particular to Perry's political strategeries: (1) his assault on higher education; and (2) his affiliation with the New Apostalic Reformation, which was behind his much ballyhooed "day of prayer" media event. In Texas, higher education has become more politicized than any state in which I've ever lived, now a target for "reform" (which means, a target for corporatization). And as for the New Apostalics, well, if you think Mormonism is a strange religion, you just wait. I urge those of you unfamiliar with this religious movement to read up and take note.

Perry is very, very scary.

of barks and turds

Music: Martyn Bates & Troum: To A Child Dancing in the Wind (2006)

I had already given myself over to imperfection long ago, but walking into the house I knew the newly vacuumed carpet offered up a turd because of the slight waft of a certain, well-known olfactory signature. After a long day of engaging the collective mind (and after a happy hour in which a colleague at a different school exclaimed how she longed for that kind of engagement in her workplace), I opened the door to home longing for an impossible clean. It's the same longing that I prepare for when I travel, cleaning the house rigorously before I fly off, so that when I come home there is some semblance of the hotel I was in.

In the back of my mind I knew the sink over there, in the kitchen, was piled with dirty dishes, but I knew I couldn't see them unless I went left into the kitchen, and I could avoid that path and walk straight up to the bedroom on the right for a change of clothes. Between me and the comfort of pajamas, still, was evidence of my failure to potty train a creature a fraction of my weight (in pounds and bad ideas). A singular crescent of brown-dried excrement in an otherwise almost-magazine-worthy living space (the magazine would be an alternative rag, of course, not Elle Decour) would be a reminder, as all excreta are, of the necessity of tolerance, or responsibility. "I'll get it later," I thought to myself, as I tore off my bowtie and launched upstairs to escape the hidden but uncomfortable truth-fashion of swamp-butt.

(Swamp-butt is a local coinage for the damp trousers that are an inevitable consequence of the Texas climate in August and September. It's a kind of open secret that if you are living here you will sweat, and the sweat will be wicked, and that your wicking is probably on display but everyone pretends not to notice its sight or smell. Austin is a metaphor for sweat.)

Yes, there is a dog turd in the living room, but as any dog owner (or owned) person knows, poop comes with the territory; being the recipient of unconditional love has its price. And if I had a guest in my tow, this might be embarrassing, but dry and comfortable clothes take priority in the audience of the Self, tired and waiting it out for bed---because, really, who goes to bed by nine? (Oh, right: my mother). To coin a phrase: the turd, like heaven, can wait.

As it has for some hours, until I started thinking about allegories for a reluctant adulthood, and the memory I had repressed---that there was a turd in the living room---came to mind, and I started writing this. A confession: two paragraphs ago I secured a paper towel and removed and dispatched of this reminder of mortality [note: originally the word I wrote here was "morality," and there are no mistakes in the interior]. Now I sit on the patio, smoking "just a cigar," and the dog sits at my back on the bench. When we first met and I agreed to take him in, I would become enraged at the sight of his many "gifts," which he deposits sneakily, like some foul counter-Santa, but after some years I've developed a strange ambivalence, a strange ambivalence charitably read as tolerance, but perhaps better labeled as laziness. Sometimes---ok, many times---I reason that if I let the dejeta ripen, it will harden, and make it easier to remove.

But, he is a dog, after all. A dog that was abused in some former life; I've only been able fashion some glimmer of his former life (and we humans want our history). It involves, I think, life spent in a crate and a man who did unpleasant things with a belt. It's an educated guess (I've done pet rescue for almost a decade). When I pull out a belt in some disrobing ritual, he cowers. If only he could talk.

But he does not talk. He barks. Sometimes, he barks a lot (ergo, the nick-name, "Sir-Barks-A-Lot"). And as best as I can discern, these barks translate thusly: "Look at me! I can bark! And I can bark now without some man lashing me with a belt!"

Sometimes he will set off barking, and the barking begets the impulse to bark anon (and on and on), and we will be in the patio, and he will want to be let inside, and he will run laps around the living room barking at no thing in particular; he's just barking to bark, because he can, because the barks beget barks, because the barks almost seem to be in response to a previous bark, and because I'll let him, closing the door, thinking of the Rolling Stones (Get Yer Ya Yas Out). And wishing I could do that too.

It's the difference, really, between the Beatles and the Stones. One lives comfortably as the next-door neighbor. The other, in the street, loud and living and taking punk to the bank (or the cops). Love-ins? No. Stand-outs. Ruff ruff. Street shouting man. And all that jazz.

But what would the neighbors think? We share walls. I cannot bark. So, you know, I sing and whistle, musiking noise and crafting a melody.

An emerging scholar today spoke of interruption, that the subjectivity of the maternal was crafted by (or brought into being by) the impossible refusal of the parent who hears a cry. Levinas, presumably. (Not "the call," mind you, but "the cry," the hailing that demands an unthinking reply of recognition.) Phatic responsivity, if you will. The maternal cannot refuse the demand, when the maternal is located beyond the self-consciousness of volition, to some hard-wired place, presumably.

How frightening to think of Selfhood in such a way, and yet, how liberating and in some sense true. Barking to bark, for bark's sake. And then, of course, there's poop on the living room carpet. Excess, deposited. Deal with it. Deal it. Deal. That's what dogs do (in both senses). And that's what people do---at least, that's what they do when acting out in groups.

Of groups and poop: a certain willed blindness, for the intoxication of knowing what to do. A clean house bereft of the evidence of pets is a house that is not lived-in, only staged.

The garden out here droops as I contemplate sleeping and walking into a house that reminds me of struggle, and not only my own. As I picked up the poop I was reminded of my fortune, that the discomfort of my living is that of poop on a carpet, and that I'm not worrying about bombshells landing in the pepper plants. It is a luxury that worrying over a rescued dog is my chief discomfort. I guess that I'm grateful that I'm not in Syria.

it's synth-pop friday!

allegory of texas politics

Music: :Zoviet*France: Collusion (1984)

Thursday night driving home from class, a young man in the neighboring lane motioned to speak with me. After I fumbled for some seconds trying to find the window's controls, I got it down and he said "your back passenger tire is going flat!"

"Thanks for letting me know," I said, "really appreciate that." I drove on it for a little less than a mile until I reached a gas station. After getting quarters from the attendant, I filled the tire back up with air and went home.

Yesterday I went to the annual "welcome back" introduction thing for my department, which is usually followed by a happy hour at a local watering hole. I parked in my assigned garage, which I hate. I think it's insulting that I have to pay over five hundred dollars a year to go to work. UT's Parking and Transportation Service, or PTS, is fiendishly nasty and frequently incompetent; on Thursday, for example, I got a $25 ticket for backing into my car space (which I'm trying to fight).

So, I return to my vehicle and, lo, the back passenger tire is completely flat. In 110-degree weather, it is now my lot to change a tire. Which I do (thankfully, not in the sun, but still it was sweltering). As I was changing my tire, which took me about 25 minutes, three PTS service carts drove past me. A ticket writer passed me about nine or ten times making the rounds in search of the smallest infraction. I made eye contact with him, and one of the service cart drivers. Not one person stopped or offered to help.

That attitude, my friends, is Rick Perry. If you elect this guy, America, you're going to not only pay, but suffer if you ever get down and out . . . .

it's synth-pop friday!

compensation

Music: The National: High Violet (2010)

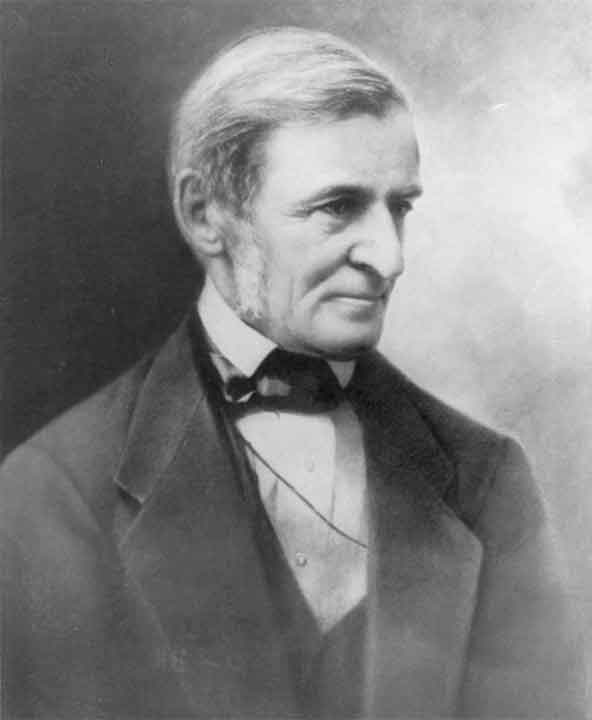

A happy sight is a toad in the garden, which means things that annoy are getting eaten. But a toad in the garden often means worry, because the dog wants to interrogate the toad, and the toad can spray toxins, which could inspire an expensive vet bill. I am charmed by inspired veternarians about as much as I am inspired Volkswagen repairmen. And in this way, Ralph Waldo Emerson's observations creep into my so-called patio-ed life. Polarity.

A happy sight is a toad in the garden, which means things that annoy are getting eaten. But a toad in the garden often means worry, because the dog wants to interrogate the toad, and the toad can spray toxins, which could inspire an expensive vet bill. I am charmed by inspired veternarians about as much as I am inspired Volkswagen repairmen. And in this way, Ralph Waldo Emerson's observations creep into my so-called patio-ed life. Polarity.

The Concord Sage penned "Compensation and Self-Reliance," an oration published as a pamphlet (as was common in the nineteenth century), to better clarify his promulgation of "independence." (In his time, Emerson was probably better known as an orator than he was as a writer.) He opens with a rather epic poem (not to my liking), and then says:

EVER SINCE I was a boy I have wished to write a discourse on Compensation; for it seemed to me when very young that on this subject Life was ahead of theology and the people knew more than the preachers taught. The documents too from which the doctrine is to be drawn, charmed my fancy by their endless variety, and lay always before me, even in sleep; for they are the tools in our hands, the bread in our basket, the transactions of the street, the farm and the dwelling-house; the greetings, the relations, the debts and credits, the influence of character, the nature an endowment of all men. It seemed to me also that in it might be shown men a ray of divinity, the present action of the Soul of this world, clean from all vestige of tradition; and so the heart of man might be bathed by an inundation of eternal love, conversing with that which he knows was always and always must be, because it really is now

Emerson goes on to indict a preacher he overheard for assuming justice and right is not now, but in the hereafter. Emerson finds grace in the moment, in the here and now, in the toad in the garden, warts and all that jazz.

I discovered Emerson at that moment in my young life that I knew I could read and comprehend. I was probably in fifth or sixth grade, I think, and I was at a used book store and this little (that is to say, conquerable) book stuck out, "A Revell Inspirational Classic," and my mother bought it for me. I read it in an afternoon and, I recall, didn't understand much of it at all. I came back to the book in high school, and was charmed by Emerson's critique of mainline religion. My junior year in high school "Compensation and Self-Reliance" was very important to me as I left the church. I then had a year-long obsession with Ayn Rand which was, thankfully, crushed out of me my first year of college after a crash-course with Nietzsche's work.

Still, I'm surprised by Ralph Waldo's influence, working like a little motor, beneath my thinking. I was just a while ago sitting on my patio, starting to smoke a cigar, when the toad came and the dog went after it. Emerson's "Compensation" essay popped into my head, and for a moment I was transported back to the basement of my parents' home. I am sitting at a table set up against a window on a concrete floor. The pine-studded wall-frames are made into walls by black plastic. A box fan is set into the west window, and I am sitting next to it smoking cigarettes and reading Emerson and convincing myself I know what the hell he is writing about . . . . I think, at 38, I understand what he is saying now, and I don't necessarily like it.

But at 17 I liked what he was writing very much. I was also fascinated with Joyce. I read Ulysses. Twice, smoking and sitting by that window, the fan sucking out the smoke so that my parents wouldn't notice. (My parents told me, years later, they did indeed notice.)

But now I wonder. It's funny how formative what I've read in my teenage years has been to my current thinking. Emerson appealed to me then because of his strident call for non-conformity; for him, self-reliance meant abandoning dogma, and I was very much about doing that at 17 (I was a teenage goth/debater---hear me roar!). But for "compensation." The toad on the patio inspired me to fetch the book from my collection (I will never part with this book), and skimming I'm reminded he had much to say that critiqued what passes for individualism today. Emerson's conception of the divinity within all of us required compensation, or rather, a recognition of some kind of cosmic dependency on the Other, which in turn required a form of generosity of spirit. Not a reliance, mind you, but rather a recognition that you are not alone, and without others you were not participating in the dynamism of the divine.

It's not lost on me that many of Emerson's most famous orations were delivered in Masonic temples.

I write this with the ramping-up presidential campaign in mind, of course. Today I've been reading about "black liberation theology" and sermons of Jeremiah Wright, which I find quite moving. Emerson had a lot to say about religion and it's political import, and it has more common cause with "black theology" than it does the so-called Tea Party. I don't mean to claim Emerson on the right side of history, but still, his words make me think.

it's synth-pop friday!

on popular fellatio

Music: Not Drowning, Waving: Cold and the Crackle (1986)

The corndog bitten and then seen around the world, thanks to the Intertube virility, came from the Iowa State Fair many days ago. The biter is one Michelle Bachmann, the current presidential candidate favored (apparently) by the "Tea Party" flank of Neoconservativsim in the United States---not the Republican Party, per se, since it seems many former re-pubs have declared their independence. Admittedly, when my friend Mirko passed on a link to this photo I lost myself to fits of adolescent laughter; I even posted the photo for a few days as my profile picture on a social networking site. I replaced it a couple of days later with an image of Rick Perry eating the same for balance, but the image is not as funny. I then asked myself: why? Why is Perry stuffing his corn-hole with a dog not as funny as Bachmann doing the same?

The corndog bitten and then seen around the world, thanks to the Intertube virility, came from the Iowa State Fair many days ago. The biter is one Michelle Bachmann, the current presidential candidate favored (apparently) by the "Tea Party" flank of Neoconservativsim in the United States---not the Republican Party, per se, since it seems many former re-pubs have declared their independence. Admittedly, when my friend Mirko passed on a link to this photo I lost myself to fits of adolescent laughter; I even posted the photo for a few days as my profile picture on a social networking site. I replaced it a couple of days later with an image of Rick Perry eating the same for balance, but the image is not as funny. I then asked myself: why? Why is Perry stuffing his corn-hole with a dog not as funny as Bachmann doing the same?

In part, it has to do with the closed eyelids and what that signifies. You have to be familiar with pornography to know. I know only a few of us are familiar, of course. If you need an explanation, email me.

So far, the smartest commentary I've come across has come from a conservative website. The shot was taken by a reporter for UK's Telegraph, a fairly respected paper (akin, I would reckon, to the Washington Post, a little left, but respected). The Mediaite website commentator, Frances Martel, asks the rhetorical question, is this the best photograph The Telegraph could come up with? The answer is obviously "no," so Martel concludes two rationales: (1) Bachmann is actually photogenic, and this is the "liberal" MSM's attempt to destroy this quality; and (2) there is a sexist subtext. Regarding the latter claim, Martel suggests no male candidate would be similarly portrayed.

I think Martel's second point has some teeth; I thought the same thing with the now infamous Newsweek cover photo of "the Queen of Rage." As difficult as it is to admit it, I worry that what prompts my laughter at Bachmann CornDogGate may be an internalized misogyny that is part of what it is to be a subject in the United States (if not the West, or perhaps . . . .).

My worry, in part, is inspired by a recent essay by Karrin Vasby Anderson in the recent Rhetoric and Public Affairs journal titled, "'Rhymes with Blunt': Pornification and U.S. Political Culture." In this essay Anderson analyzes political discourse surrounding Palin and Clinton in the 2008 election and persuasively argues that sexualized stereotypes have emerged in popular venues to contain feminine gains in the political arena. She tracks something I've been noticing as well, the reduction of the female politician to the "bitch," or worse, to that which rhymes with "blunt." Quick proof: the photograph of Bachmann eating the corndog. Although I think I probably come at feminism from a different tack than Anderson (I'm a "pro-porn" feminist, as they say, and on board with the third-wave queer studies ilk), I nevertheless think she's tracking something disturbing and important---and that her essay is quite prescient for the looming election cycle: misogyny is a political weapon in popular culture, right and left.

See, here's the deal: my inner twelve-year old laughs at the Bachmann photo because, well, it's dirty and I do not share her political viewpoint. In fact, I find her platform offensive and scary, and so my laughter is produced by the intended photographic-pornographic signification: this is a female candidate who is demonstrating her subservience to patriarchy, despite herself. The telegraphed message is that Bachmann's candidacy, presumably a feminist achievement, is really a patriarchal gesture. And there's something to that implied "visual" claim, no doubt. But, Martel is right: the decision to publish the photograph (evidenced by the text accompanying it in the Telegraph) rides a number of sexist assumptions, assumptions that Anderson details very well in her essay.

Well, my reaction here is complicated. I cannot discount how clever the "visual rhetoric" of this image is, because few of us who side on the "left" would agree that Bachmann represents a progressive view of women and their import to the socious. The image is funny in this respect, and I understand the high-minded commentary that was, apparently, intended. At the same time, the politics of representation here is troubling for the reasons that Anderson points out in her conclusion:

Humans have always been storytelling animals. As critics, we consider not only what stories teach us, but also what they reveal about us. Unfortunately, this particular story demonstrates that if you're a woman running for public office, you're just a few jokes away from becoming a . . . well, I can't write it here, but it rhymes with blunt.

It can't be put more bluntly. Brilliantly put.

I don't want Bachmann to be president. But I worry about the attempts to prevent that reality this way. I worry about the "left" (in journalism or otherwise) riding misogyny for political gain. It was done to Clinton and Palin in 2008, and it's going to be done to Bachmann in 2012. There are reasons a-plenty to disqualify this person from public office other than the fact she is a woman. Even if I find the photograph funny, I have the self-awareness to know what ideology is appealed to with this image.

The left can do better.

perry and political totalism

Music: Edward Ka-Spel: Tannith and the Lion Tree (1991)

Here we go. Perry has announced himself the Grand Old Party's messiah. Good hair. Handsome. He appeals to the extreme and the less extreme. Christian. White. Resolutely phallic. Did I mention good hair? The man (and his team) has crafted an image of absolute autonomy. The hope: the public (pubic?) pendulum that swung toward reconciliation will now be drawn back, irresistibly, to the Big Dick. And we thought Bush was a prick . . . .

I'm not going to be optimistic. Demagoguery works. It worked for Obama. It will work for Perry. It will not work for Bachmann because she is a woman (case in point: the relentless publication of unflattering photographs). This election will be a "man-thing," and I do understand. I don't like it. But that is the way this seems to be going down.

When I moved to Texas in 2005, it was quickly obvious my new governor had aspirations for the presidency. Unlike most governors in the states I've lived in (Georgia, DC, Minnesota, Louisiana, and Texas), Perry would periodically concoct some sort of media event in which he did something patently absurd yet within the seething, widening horizon of "common sense" for the "far" right. It was obvious to most living in Texas that Perry was readying for a bid in 2009 when he announced that Texas may have to secede from the Union because of continual federal meddling in state affairs (this, despite his taking federal dollars to balance the state budget twice). I remember a number of us laughing over dinner about this media stunt, designed to get the attention of the southern "conservative" (secret Confederate) block Houston Baker, Jr. warned us about in Turning South Again. We discussed, I dimly recall, Perry's strategy would be to rally the southern bloc, a strategy that has won a Carter, a Clinton, and two Bushes national contests. The "southern mind" is, as Cash observed, a complicated thing, but as Baker argued, the south has also dominated national politics for decades. If I ever get into teaching "politics" (whatever that is) in my classes, I will try to focus on making sense of the role of the psychical South in electoral politics. It's just perplexing, but empirically undeniable. There is something Confederate about Perry's promise, something racist. It's there, and it's soul-deep to his appeal, and I can't quite figure it out.

Nevertheless, Perry has finally admitted he's "all in," even though most Texans knew this: almost all of the legislative wrangling at the state level has been done with the understanding of a national audience (and a coming scrutiny in years to come): immigration; demands for disaster funds (and their mismanagement); education reform; death penalty; "a day of prayer"; the list goes on and on. The good news is that Perry has a lot of skeletons that are going to come out (for example, read this polemical essay that details a number of icky things he's done; I do not like how this is written, but the basic points are factually based I lived through almost all of them). Bachmann's skeletons are pretty much out there now, for all to see; Perry's have been strangely kept put up.

The bad news is that Perry is scarier than any politician I've been frightened by: all you folks who don't live in Texas hear me out. If you thought Bush was bad, Perry is worse. Much worse. I found Bush II as odious as many folks did, but I never lost sight of his humanity. I'm not so sure, however, I can say the same for Perry. Bush, at least, is not a dull man (despite what some people claim); Perry . . . well, I think he's met his match with Michelle Bachmann.

He is not a stupid man (no politician of national stature is stupid, when we define intelligence broadly). He is, however, not a "cognitively complex" person; he is in this respect the antithesis of Obama (if you ignore the fact they are both "male"). Perry does not play with a lot of cognitive categories; he's "black and white," and in more ways than one. Cognitive complexity refers to the avenues of thinking, or how many concepts one can juggle at once when making political decisions. The recent deadlock in Congress over the debt ceiling was couched in arguments about cognitive complexity: seasoned Hillers were saying these uncompromising "freshmen" Tea Partiers didn't understand the political process of compromise. That's just code for "it's more complicated than you think." Perry is not about complicated. Perry is about unwavering principle---even when those principles are contradictory.

I read a brilliant article by Kenneth Rufo and R. Jarrod Atchison this weekend that helped focus my thinking on Perry. Their essay, "From Circus to Fasces: The Disciplinary Politics of Citizen and Citizenship," recently published in The Review of Communication, ostensibly tracks the "casual imprecision" of the deployment of the concept of "citizen" in my field, communication studies. They argue a rather imprecise deployment of the concept of citizenship in my field over the last century---a concept deployed early on as the justification of the field's existence, to produce "engaged" citizens---has both contributed to and tracks a sort-of enlarging of the political domain (or the dominion of the political). From a disciplinary vantage, they discern we have a bi-polar understanding of the "citizen" that is a symptom of the ideology of the "political": on the one hand, there is a lack of political engagement among "citizens" and our role is to educate toward political participation (modernist model); "On the other hand, we have a discourse theory of citizenship that sees all citizens as incorporated into the body politic"---the political produces the subject position of "citizen." Both ways of thinking, they worry, implicate an hegemony of the political (one has us moving there, one has us there already) that is troubling:

If our feeling of foreboding seems absurd, it does so because of two historical trends. The first is the apotheosis of the political in the 19th and 20th centuries, starting with the massive spread of enfranchisement and the increasing demand for inclusion within the political process. Hence, slogans like "everything is politics" or "the personal is political," wherein the implication is that every action carries with it political realities, consequences, or overtones. One's choice of church, a kindness to a stranger, the goods or services we consume, the entertainment we enjoy, the food we eat, the way we dress, the way we vote, the way we argue, what we argue about---all are political acts. The political has become so pervasive that it has become commonplace to assume its status as the unsurpassable master horizon of our age.

The second trend, they note, is the assumption that democracy and totalitarianism are at odds (and they remind us that Hitler came to power by the ballot).

I don’t want to put words in their mouths, but it seems to me Rufo and Atchison's implication is classically Gramscian: intellectuals also do the dirty-work of the dominant class, however unwittingly.

I'll leave the disciplinary concerns of the essay for another moment (I'm personally not as invested in the debates over citizenship in my field; it is a sacred cow, but it's not one I want to milk or make into hamburger). What their analysis helps me to see about politics in Texas, or should I say, Texas National Politics, is that both trends are pretty damn stark with Perry in the key of "double-plus-good": like many of the Tea Partiers, he's running on a platform that purports to limit the reach of the political (here, understood as the state/power) by promoting political excess, the complete collapse of the work of the state with lifestyle, modes of consumption and social reproduction.

I'm not saying we don't see this on the left too, we certainly do (First Lady public health campaigns come to mind). But Perry and Bachmann are particularly conspicuous examples of political excess: Perry's "day of prayer" spectacle last weekend, asking us to atone to God for our sins, or Bachmann's now widely seen photograph of her devouring a foot-long corn dog at the Iowa state fair. If there is such a thing as abject irony, it is the politician calling for the autonomy of "ordinary citizens" while wanting to legislate every cultural expression of private living under the sun (Perry was a defender of the Texas sodomy law that was struck down, for example). And don't get me started on Sarah Palin's "reality television" show. "Total politics," the idea that everything from consumption to popping the zit on your lover's back is a political act, represents a certain ideological collapse that Rufo and Atchison identify as a looming fascism. I think they are right.

In his classic and (seemingly unendingly) useful essay "The Work of Art in the Age of (its) Reproducibility," Walter Benjamin ends on a frightening yet somewhat hopeful note. He says that the danger of his time (the decline of the Weimar) was the aestheticization of politics: the Nazi's were making politics into an art. This amounted to, Benjamin hinted, making death look pretty. If you can make death look pretty, horrible things can happen (and he was right; they did). He suggested we needed to politicize art (and he had film in mind). Well, we've politicized art. Excessively. Lady Gaga got the memo.

In our time, when politics is not just art, it's now everything, most especially consumption. Perry is marketing himself as a middle-way flavor. If there's any hope for Obama (who I will vote for as the lesser of two evils), it has to be about soldiers, not the economy. Good hair sovereigns of fashion are death machines in phallic clothing. Somehow we need to convince others that politics is not taking your own canvas bags to the grocery store or where you buy your latte; politics is more about the kind of killer you elect.

letter to zarefsky

Music: J. Geils Band: Love Stinks (1980)

Background: Last summer I gifted David Zarefsky, a widely respected rhetorical scholar known for a seminar he taught for decades on Lincoln, this t-shirt. He loved it. Since then I've been stockpiling strange Lincoln memorabilia . . . .

Dear Dr. Zarefsky,

I regret I could not afford to attend the public address conference this year, especially because you were the honoree. I remain a fan of your leadership and scholarship, and wished I could have been there to applaud you and share in the "love bubble" that is the banquet at that conference. I'm hopeful, however, my tradition of sending you unsual gifts might make up for my absence last month. I spied Lincoln in Austin. He was in the H.E.B. H.E.B. stands for "Harry E. Butts," the original owner of a chain of grocery stores in Aus-Vegas (you may recall upon your recent trip to the LBJ library buying something in one close to campus). Of course, savvy promotional peeps at the company have resignified the chain to "Here Everything's Better," as if the original pun can be eradicated. I spied Lincoln not on someone's backside, however, but on the side-side. An arm, to be more precise. I approached this young man in the H.E.B. and said, 'Excuse me. That is a rad tattoo. Would you mind if I took a photograph? I have a colleague who studies Lincoln who might appreciate seeing this." "Yeah, go ahead." As I readied the shot I asked, "Why Lincoln? Are you a fan?" He replied, "yeah," but was quickly interrupted by his girlfriend, who was bagging their groceries. "Oh, don't get him started on Lincoln---/please/!" And so, attached, a little tattoo that made me think of you. With affection, Josh

Dear Josh,

Thank you very much for this latest memento, although I am not quite sure just what to do with it. I am not sure that the wearer of this tattoo would be safe with it in some parts of Texas, but I will take what I can get.

I remember H.E.B. from visits to Austin while I was growing up in Houston, but I had always thought that the last name was singular.

[snip personal details]

Best regards,

David

it's synth-pop friday!

on publishing: parrhesia

The following post was made over on The Blogora. I'm posting it on RoseChron for readers who would like to respond but prefer a smaller audience. _______

This past June Jim Brown posted about his troubles with the length of peer review; he complained it was taking up to four months to get reviews of manuscripts. I chimed in that it was taking not months, but years to see something through the review process. I now tell aspiring scholars to anticipate at least a year, probably closer to two, for a piece to go through review and get published.

This advice may seem far-fetched, but I have too many examples to prove the exception has now become the rule. Attempting to be the parrhesiades Foucault writes about in Fearless Speech, I think it's fair to say the worst peer review experience I had was with the . . . Quarterly Journal of Speech in 2005/2006. I had a psychoanalytic piece there that languished for over a year; countless queries to the editor went unanswered for months (prompting me to complain to the NCA research board). Then, the essay was rejected on the basis of a review that claimed my piece would do irreparable harm to public address (hardly the best fit as a reviewer). I've had manuscripts lost and languishing at Philosophy and Rhetoric and the Journal of Popular Culture for over a year, too. A manuscript at Communication Theory went un-reviewed for two years until a new editor took over because the previous editor "had a nervous breakdown." I had a piece in revise-and-resubmit limbo at Critical Studies in Media Communication drag on so long (again, over a year) that my co-author and I pulled it and I resigned from the editorial board. And I have many more stories about long delays and irresponsible reviewers, but my most recent experience at Text and Performance Quarterly, a NCA journal, is a good illustration of what has become, at least for me, the "new normal" in publishing.

September 28, 2007: I submit a manuscript to Explorations in Media Ecology.

August, 2008: Reviews for submission to EME are finally in; the editor recommends that I revise and resubmit. Incidentally, this manuscript inspired the nastiest review I have ever received.

August 2009: Editor of EME resigned, so I decided to pull the manuscript and revise for a different outlet. I didn't revise for a whole year, so it's just as well. The editor and I were in touch throughout the year, and finally I just told him I would pull to save him a transitional headache.

March 29th, 2010: I submit a substantially revised version of the manuscript to Text and Performance Quarterly.

June 2010: I inquire about my manuscript. I'm told by the editorial assistant to be patient and that the editor is in Greece and one must consider the "demands" and "responsibilities" of reviewers (he obviously doesn't know I review about 15 manuscripts a year myself; more of my complaining here).

August 9, 2010: I inquire about my manuscript again:

From: Joshua Gunn Sent: Monday, August 09, 2010 12:48 PM To: Editorial Assistant Subject: RE: TPQ

Dear [Editorial Assistant],

I submitted my manuscript ["Catchy Title"] twenty weeks ago today. I'm writing to ask, again, where we are in the process of review. You'll recall I inquired about six weeks ago.

Sincerely,

Josh

Instead of hearing back from the editorial assistant, however, I heard back from the editor:

Date: Mon, 09 Aug 2010 19:17:29 From: Editor Subject: RE: TPQ To: Joshua Gunn

Dear Josh,

I'm so sorry for the delay with your manuscript. One review has been completed. The other referee notified me early in the summer that s/he would be unable to complete the review. As I'm sure you can understand, summer can be a difficult time to secure reviews, and my invitation to review your piece has only recently been accepted by a second referee. I would like your manuscript to benefit from two reviews, and thus I hope that you can wait a while longer.

I appreciate your patience and please don't hesitate to contact me if you have further questions.

best,

[Editor]

August 17, 2010: I finally get the reviews of my manuscript. I receive a "Reject & Resubmit" (a new one for me--what is that, exactly?) with the suggestion that I revise to make "reviewer 2" happy (reviewer 2 completely misunderstands my argument and is hostile to psychoanalysis). I email the editor and inquire if I really should revise, because I don't think I could make reviewer 2 happy at all. "Thanks for writing," s/he responds. "I know that Reviewer 2 asks for a lot--but I don't think s/he is anti-psychoanalysis in the way that the other reviewer states. . . . I guess what I'm saying is, look for where you make claims that do need more support or more connections, and pull from Reviewer 2 wherever you can. Even if you don't agree, see how you can make your argument stronger to address and counter her/his views." This is both reasonable and polite, and I take it as encouragement. So, I revise. And revise. And read a bunch of recommended stuff. And revise.

February 13, 2011: I resubmitted a substantially revised manuscript. Since some graduate students were matriculating, the fall semester was a gauntlet of defenses. I needed the holiday break to have the time to really get the thing in top shape. Finally, in the mood for love, I hit "submit" at the publisher's website for the journal.

May 30, 2011: I decide to inquire about the status of the manuscript:

From: Joshua Gunn Sent: Monday, May 30, 2011 3:01 PM To: Editor Subject: RTPQ-2010-20

Dear [Editor],

Going on sixteen weeks ago I submitted a revised version of my speech recording essay. I know you leave for Greece in the summers, so I wanted to try to catch you before your globetrotting commences: any news on this essay?

Many thanks,

Josh

A week later the editor responds:

Date: Mon, 06 Jun 2011 04:42:07 -0400 From: [Editor] Subject: RE: RTPQ-2010-20 To: Joshua Gunn

Hi, Josh,

I am indeed in Greece as we speak/write...I have one review of your revised essay. Unfortunately, additional requests for reviews were not successful in the earlier spring--hence the continued delay. There is currently a second review underway, and that review is due back in early July. Your essay is one of a handful that I'm doing my best to keep tabs on either because reviews are late or reviewers back out. You have every right to be frustrated with the length of this review process, and believe me, as soon as that second review comes in I'll be in touch with you.

best,

[Editor]

I responded to the editor I was not "frustrated," as this sort of thing seemed to be "normal" for me. I stressed, however, that I was recently promoted and tenured, so that makes it easier to sort-of shrug one's shoulders. Still: it's a lot of time.

July 19, 2011: The manuscript is rejected. "I regret to inform you that we will not be able to publish your essay in Text & Performance Quarterly," reported the editor. "For your information I attach the reviewer comments at the bottom of this email. I hope you will find them to be constructive and helpful. You will see that the second review raises a number of concerns. You are of course now free to submit the paper elsewhere should you choose to do so."

I responded rather curtly to the editor, inquiring if it was a new reviewer--who thought my essay was "pretentious" (and it probably is)--who helped her arrive at this decision. S/he confirmed. My response was to say her decision to base the rejection on a brand new reviewer's negative review was unfair, that the process at TPQ was unprofessional, and ultimately that is his/her responsibility and that I would share my story.

To Conclude: In this recent blow-by-blow account I've tried to be careful and avoid too much editorializing (where my parrhesia comes up short, I reckon). My hope is that readers can come to conclusions about the legitimacy of the process themselves, as well as the responsibility of the editor and reviewers during this process.

But, I do want to make a point by way of a question. What this editor said to me I have heard countless times: delinquent reviewers are routine on just about any submission I make these days. I also have reviewers who just sit on manuscripts and then bail. Instead of making the call, however, editors often try to find new reviewers. Worse, even when reviews are in, sometimes editors seek out even more reviewers on revisions, which means an author has to please even more different minds. (The latter practice really annoys me and, I suspect, represents an editor looking for a manuscript assassin; more reviewer profiling here).

Part of the problem, of course, is that my skirt is too short: I write stuff that tries to push the envelope, and given the size of our field, the only person who is probably blind in a blind review these days is yours truly. That may make it tough to get reviewers to say "yes."

My bad and pushy writing aside, there remains the larger issue. Is the problem, as Jim suggests, that blind reviewers are simply not stepping up to their responsibilities? Or, is at least part of the problem an editor's inability to make the call, even when reviews are incomplete?

I know, for example, that Karlyn Kohrs Campbell, John Lucaites, and Ray McKerrow---all editors at the Quarterly Journal of Speech---had or have policies of making the call when reviewers didn't/don't get their reviews in. Although I understand the desire of editors to get thorough reviews to help an author out, it seems to me speed is much more helpful. Speedy reviews are especially important for junior scholars in the field, who are working like dogs to achieve promotion and tenure in a very anti-higher education environment. (Here at UT "research" is under attack by a number of "conservative" policy makers, lobbyists and--gasp--regents!)

All that said: in rhetorical studies, I think it behooves our junior scholars to start planning on two-year windows for submission to publication. This isn't gonna change unless there is a concerted, discipline-wide effort to address the structural issues behind our antiquated reviewing system. We may need to move toward "team reviewers," as Jim suggests. I personally think we need to move toward all editors making calls--having a little gonadal gravitas--but perhaps that's because my personality is more Hebraic than it is Hellenic.

bar time

Music: The Decemerists: The King Is Dead (2011)

It's hot. But there is a trade. When I walk outside and look up into the Texas sky, I see blue blue upon blue and fluffy white, and its beautiful, and I find myself standing there, in the alley that is my drive, with a bag of trash in one hand and worrying if the sweat in my hands will hasten the bag's drop before I make it to the dumpster. But I was there on the run for trash, gazing into to sky, and thinking about NASA (and its temporary demise), and dozens of airplane flights I've had flying through it, and the little fluffy clouds (and Rickie Lee Jones on cold syrup), and thinking that, first, the sky was something to marvel at, and then, of course, thinking I was thinking of the sky as something to marvel at, and that I had this thing for romanticism and an a secret crush for Maxfield Parrish. But I found the dumpster; and in ten minutes it was time for a change of clothes.

Still, I stood there in the alley for a moment and looked at the sky in a way that was not shot for a movie.

I also have a thing for Lucian Frued, and he just died, and learning that news made me sad today (thanks to a Yahoo news feed). I read the paper today, but Lucian was not there. Just a cover story about the man who flew a plane into the IRS building last year, and some speculation about my university's sports team, and an interesting and guarded interview from my employer's boss (the chancellor, who seems onboard with the push toward online teaching). Sundays often go this way, directing the reflection this way, on this and that. But that sky. That blue blue sky with the little fluffy clouds. It may be a triple digit summer, but the sky . . .

The sky today was very pretty. That much is objective

.

I'm sitting on my patio enjoying a Padormo maurdo, in the last inch. I know I shouldn't smoke, and I think about giving up my current enjoyment even as I puff away. Those of us who smoke often rationalize the habit; death is close. And yet . . . .

My last cat (I had up to three at one point), the one without any hair, sits curled up on the bench. She is an indoor cat, but as she is old and a beggar, I've let her join me out here, in her final years. She's well behaved and just flops around in the heat. Watching her curled up now, I'm reminded of John Carpenter's remake of The Thing. She is not pretty. She is, despite her looks, a lovely friend. The Texas clime suits her well. I think William Burroughs would share my affections for her. I'm certain, really.

.

I've spent these past few weeks writing. I find I still have too much to say. Having the time to write has been felt-through as joy. I mean, I really like it. I enjoy writing, I find fun, to write (like I do now, though in a different mode). And maybe that's a problem or sort of psychosis. I dated a lady recently who said, "you're in your head too much." I worry writing for a living (which, let's face it, is what I do for a living) may be too isolating. As an only child, the comforts of isolation were hard won---but also in some sense forced. Learned. Incorporated.

When someone like me is social and with people for weeks on end, when there are faces to read for weeks, that moment of solitude, when it comes, is something like a home-drug. I know this house. I know the rooms. I know where to steal a centimeter of toothpaste. I know where I hide the dirt.

I'm sometimes surprised by the projections of others, of what must happen here. I'm folding laundry. We're all folding laundry. Somewhere, on Capital Hill, maybe, the laundry is forgotten and thoughts of capital gains taxes dance in their heads.