obama in myth and fantasy

Music: Marconi Union: A Lost Connection (2008)

This week I've been slammed, and I regret I've not had much opportunity to blog. In the rhetorical criticism seminar yesterday, our topic was fantasy and mythic criticism. Sometimes in my seminars I open the class with a provocative rumination on themes or class topics to stimulate discussion. I thought I'd share yesterday's rumination, as it may interest readers here too. Here goes:

This week I've been slammed, and I regret I've not had much opportunity to blog. In the rhetorical criticism seminar yesterday, our topic was fantasy and mythic criticism. Sometimes in my seminars I open the class with a provocative rumination on themes or class topics to stimulate discussion. I thought I'd share yesterday's rumination, as it may interest readers here too. Here goes:

In preparation for seminar today, I emailed my friend and mentor Tom Frentz. I said:

Tomorrow my graduate class is reading about myth and fantasy, and they're reading up on this guy, Thomas Frentz. I was thinking: if Frentz were to do a mythic criticism of the election of Obama---or the aftermath of the election---what might he say?

As Tom is wont to do, he responded within two minutes. This is what he answered:

Good question. What, indeed, "might he say?"Well, the as-in-"duh" answer would be he'd cast Obama as a hero in the Joseph Campbell mold and show the specific ways he worked through the three major phases of the monomyth---departure, initiation, and return. That would be both easy and---perhaps---fruitful.

A less obvious move would be to do Barack "intertexually" showing how he picks up on the extends the mythic trajectory past black leaders--King, Malcolm, Ali. This tact might result--I fear--in Obama's subtlely casting off those stereotyped anglo characteristics of the "angry black man" and taking on the more acceptable guise of---well---a dude who is, after all, only "half black."

Or---the most provocative move (that I can think of off the top of my addled mind) would be to compare a non-threatening black man (that would be Obama) to a very threatening (can you say "castrate"?) white woman (that would be Hillary). From this move, Obama emerges as the lesser of two fantasy evils.

Best I can do on the spot, dude. Feel free to share with your graduate class.

So I have shared Tom's remarks to my graduate class, and I would like to use his observations here as a springboard for thinking about myth and fantasy in rhetorical criticism, with the example of Barack Obama.

Unquestionably Tuesday was a remarkable moment, the culmination of the American monomyth in which Obama read the tablets offered him. In a subdued but prophetic tone, Obama purported to close a sickening chapter in American history by announcing the beginning of a new one. As Ellen Fitzpatrick remarked last evening on the Leher News Hour, Obama's victory speech resolved a centuries-long "moral contradiction" in one, singular moment, putting a period on a rambling and tortuous sentence that begin with the word slavery. Many have remarked---and some, under the tongue of cynical reason---that Obama is the material manifestation of Martin Luther King's dream of a colorblind dinner table, that Obama is the dream fulfilled. In respect to dreaming and it's most famous representative, the dream of Martin Luther King, we have something of a convergence of myth and fantasy.

Of course, I need not underscore the proximity of dreaming to myth and fantasy. As cultural stories with transnational appeal, myths regularly inform our dreams and structure our lives: the American dream, for example, is certainly mythic, and in both senses. The American dream is obviously a dream forever deferred, betokened by widespread financial crises and regular eruptions of violence (just this morning there was a shoot out between a swat team and determined youth near my home; I was trapped in my house for hours). Yet the myth of Ameritocracy still has a profound structuring and ideological power. Obama's success is said to be the fulfillment, not only of King's dream, but of the American dream. His chiseled chin rests alongside those of Oprah Winfrey and Colin Power in the black Rushmore of the popular imaginary. "Yes We Can" is resonant because it is merely a regurgitation of a dream of whiteness that would celebrate the achievement of a singular hero instead of recognize the need for community and textbooks and computers in inner-city schools.

There are other myths at work, too. Routinely one hears statements that Obama's presidency is post-ideological, which is code for post civil-rights era, post 1960s (the counterpart, as it were, to postfeminism). The flap last July over Jesse Jackson's unscripted remarks about Obama come to mind. As I've noted before, anyone remotely close to a screen will know that on July 10th the news broke that Jesse Jackson was “talkin’ trash” about Obama on FOX. Apparently unaware his microphone was hot, Jackson said to a colleague that Obama has “been talking down to black people” and that he wanted to “cut his nuts off.” These comments circulated widely because demonstrated division among blacks about Obama. The underlying warrant here is that all black people, especially black politicians, think alike and stand in solidarity. The news also created an opportunity for Obama supporters to spin this as good news: white people don’t like Jackson, therefore, this is a nice distancing moment that will draw more whities toward the Big O.

It was a shame, however, that Jackson’s “point” (pun intended) was eclipsed by his countless apologies. Jackson is angry with Obama for amplifying his “personal responsibility” rhetoric instead of focusing on larger, structural issues, like “racial justice and urban policy and jobs and health care.” What Jackson's “loving criticism” was to be about was the way in which Obama intones a therapeutic, Horatio Alger-style---or Oprah-style, take your pick---rhetoric that downplays the social-cultural and material causes of social ills---and the deeper reasons for single-parent households.

This is the Oedipal myth. The father being slayed here, of course, is a generation of male civil rights leaders, leaders who sometimes leaned on the figure of the angry black man to get things done.

The King is dead. Notably, Jackson threatened castration. Of course, from a psychoanalytic vantage castration is the power of the father, what the child fears. Castration represents one’s entrance into self-consciousness and the symbolic world. He who claims the power of castration claims the agency of language. By claiming to want to cut Obama’s nuts off, Jackson is threatening to remove Obama’s rhetorical power, to muffle his speech. The motive for wanting to do so is obvious: Jackson opposes the one Oedipal myth---Booker T. Washington sleeping with white women and killing off the Great White Daddy---with another, the myth of the primal father who has the power to enjoy.

So much for the mythic, the myth of dreams. We should also take up desires; as Lacan notes, the fundamental fantasy is only got at indirectly, through dreams. And as Frentz and Rushing would note, the dreams of a people are on its screens. Thus we find Obama's bid for the presidency compared to a film plot, over and over again.

The fantasy structures that run through Obama's successes are certainly intriguing. Although myth and fantasy overlap, the latter is libidinal; fantasies concern what it is that you and I desire. Understanding fantasies as scripts for what it is that we desire, it is not difficult to reconstruct the fantasy that structures Obama's success. At some level, King's dream spells out the fantasy of miscegenation, the desire for racial integration broadly construed as an erotic appeal, and Obama's mixed race is a literal embodiment of such a fantasy. Romancing the mulatto, however, goes much deeper in America's reconstructive past; it is a response to the mythos of the Angry Black Man, a mythos, however ironically, that arose to combat what Houston Baker Jr. might term the Family Romance of Mulatto Modernity.

In other words, have seen this kind of black fantasy before. Born in 1856 of mixed race, Booker T. Washington would quickly become one of the most prominent African American leaders by his death in 1915. Hand chosen by a white patron to run the Tuskegee Institute, Washington had many friends in the white community. Although he privately funneled money into desegregation efforts, he publicly presented himself as a friendly dandy, arguing for a more cooperative approach with whites to slowly begin building legal and social equality. Baker is at pains to show how Washington's assimilationist and conciliatory approach served to mask and muffle affective affinities among blacks. Such an attitude---this fantastic Mulatto modernism---would eventually give way to quiet anger of Washington's rival, W.E.B. Dubois . . . but not until the late 1960s.

As Mark A. Reid has argued, the fantasy of the angry black man goes back a long way, but it is given material manifestation in grassroots organizations from the 1960s. In 1966 Stokeley Carmichael would be elected the head of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee, an irony because he would eventually advocate retaliatory violence. In 1966 the Black Panther Party for Self Defense was formed, signaling a growing militancy among young blacks. Malcom X dared to recommend aggression. Just prior, inner-city rioting such as that at Watts on the 9th of August, 1965 helped to create the fantasy of the angry black man---the potentially violent angry black man.

The riots were televised; images of angry black people circulated widely.

It was thus in the early 1970s that the imaginary figure of the angry black man traveled from the streets to the screen. As Reid demonstrates in a number of essays, the black action hero emerged at a time when the Black Arts Movement began to vocally reject "art that tried to appeal to white America's morality." Thus 1971s Sweetback's Baadassss Song debuted in black theatres (NWS trailer is here). Reid argues that Melvin Van Peeble's film drew on "urban hero folklore" to develop the Sweetback character: he is a character who is "skilled in performing sexually, evading the police, and fighting. Unlike most white heros of the action film genre, Sweetback participates in sex to survive, and he performs with both white and black women. . . . Like mythic urban heroes, Sweetback directs violence against unjust white authority figures."

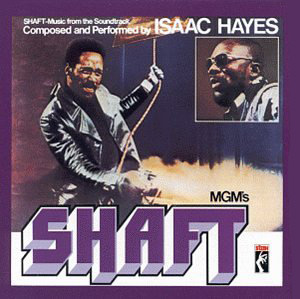

The follow-up to this action hero fantasy, however, is quite telling. Directed by Gordon Parks and scored by Isaac Hayes, Shaft notably toned down the angry part of the angry black man figure; in fact, he works with whitey to bust bad guys of color, and while he is familiar with Harlem, he lives in Greenwich Village. Of course, this was a major studio release (MGM I think), so with much care the film was softened to appeal to whiter audiences. The fantasy here is, again, mulatto modernism: a black man who upholds white American morality.

The follow-up to this action hero fantasy, however, is quite telling. Directed by Gordon Parks and scored by Isaac Hayes, Shaft notably toned down the angry part of the angry black man figure; in fact, he works with whitey to bust bad guys of color, and while he is familiar with Harlem, he lives in Greenwich Village. Of course, this was a major studio release (MGM I think), so with much care the film was softened to appeal to whiter audiences. The fantasy here is, again, mulatto modernism: a black man who upholds white American morality.

With reference to these two black films, perhaps in some sense representing the threat of Malcom X and the comfort of Martin Luther King respectively---as they were framed for television audiences---we can come to see the fantasy that holds Obama aloft, indeed, the fantasy structure that helped to elect him: Barack is giving us the Shaft, with a little Booker T. thrown in for good measure.

In his book, Dreams of my Father, Obama admits to cultivating such a fantasy: "I learned to slip back and forth between my black and white worlds . . . One of those tricks I had learned: People were satisfied so long as you were courteous and smiled and made no sudden moves. They were more than satisfied; they were relieved---such a pleasant surprise to find a well-mannered young black man that didn't seem angry all the time." He worked on the south side of Chicago, but lives in the well-to-do Kenwood neighborhood---one of the architectural gems of the city and which neighbors the UC grounds of Hyde Park. Remember, Shaft didn't live in Harlem, either.

Of course, as James Hannaham of Slade reported in September, the conventional wisdom on the political trail was that "Obama isn't angry enough." Huffington wanted Obama outraged at Rev. Wright, joining the voices of others that would "promote a Hollywood notion of how black men should react to injustice"---that is, with anger. Obama refused to rely on such a fantasy, such a figure, which he might taken very far---into outright demagoguery and Huey P. Land (that's Long, not Newton).

Make no mistake about it, however: in opposing the fantasy of the angry black man with the Shaftification of Booker T., Obama's efforts evoke and overdetermine another fantasy that is so deeply articulated to young, political heroes it almost goes without mention: who will assassinate Obama? This is a fantasy that already has been traversed, and that will be subject to traversal again and again. We ought not be worried about the red phone; we should be worried about the pin hitting the shell.