naked life

Music: CBS Early Show

Today shall be spent (a) waiting for the plumber as a consequence of a series of minor plumbing malfunctions (the consequence being no hot water—indeed, no water at all—and the unflushable and unsightly guest turd); (b) grading; (c) writing/reading Agamben. Regarding the parenthetical turd of (a), I am convinced that "naked life" finds a representative anecdote—or perhaps, a token remainder. Isn't it curious in the mad rush to combat naughty dualism and embrace "body" that the dirtier aspects of continental are not written about in our "importation" . . . .

Today shall be spent (a) waiting for the plumber as a consequence of a series of minor plumbing malfunctions (the consequence being no hot water—indeed, no water at all—and the unflushable and unsightly guest turd); (b) grading; (c) writing/reading Agamben. Regarding the parenthetical turd of (a), I am convinced that "naked life" finds a representative anecdote—or perhaps, a token remainder. Isn't it curious in the mad rush to combat naughty dualism and embrace "body" that the dirtier aspects of continental are not written about in our "importation" . . . .

Dr. M, Tremblebot, Lil'rumpus, and Ken: y'all rock! Thanks for chiming in with your takes on zoe and bios. Here's what I wrote last week but was uncharacteristically sheepish about throwing out there:

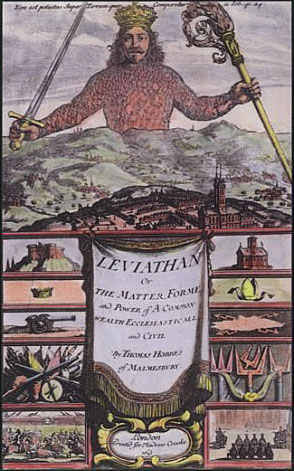

Unlike Hobbes, Rousseau, or Schmitt, Agamben's understanding of human being is anti-essentialist and anti-identitarian, which leads him, in the end, to argue against the idea of sovereignty on the basis of what some have termed an immanent ontology of potentiality. Space limits discussing this ontology in any detail, however, a brief sketch will prove helpful. In much of his recent work Agamben advances an understanding of human being as an existential potentiality, abandoning the essentialism of "human nature" and the logocentric notion of identity that informs it. Human being is to be understood as "the single ways, acts, and processes of living" that are only possibilities, never determined or given in advance. Agamben argues thatEach behavior and each form of human living is never prescribed by a specific biological vocation, nor is it assigned by whatever necessity; instead, no matter how customary, repeated, an d socially compulsory, it always retains the character of possibility; that is, it always puts at stake living itself. That is why human beings—as beings of power who can do or not do, succeed or fail, lose themselves or find themselves—are the only beings for who happiness is always at stake in their living, the only beings whose life is irremediably and painfully assigned to happiness.

In a strongly qualified sense, one is tempted to characterize Agamben's understanding of human being as being on this (left) side Rousseau in spirit, except that for Agamben the sovereign is always involved in a kind of slight-of-hand that threatens human being in the name of protecting it. "Political power," says Agamben, "founds itself—in the last instance—on the separation of a sphere of naked life from the context of the forms of life," thereby cleaving human content and form, as it were, or eroding what we might term "the good life." The content, or "naked life" (zoe), and the form, or "the manner of living peculiar to a single individual or group" (bios) are separated by the sovereign, who establishes his or its power by meting biological and political death. The power to mete life and death can only be established if one has the power to define life, or what constitutes a valuable life. Agamben suggests that such is the function of the modern sovereign: it decides what lives are worth living (e.g., citizenship) and what lives are merely bare or naked lives and therefore dispensable. "A political life, that is, a life directed toward the idea of happiness and cohesive with a form of life," continues Agamben, "is thinkable only starting from the emancipation from such a division, with the irrevocable exodus from any sovereignty." The second reason why the assertion of sovereignty is problematic is because its materialization has changed consequent to the emergence of what Foucault termed "bio-power." Blah blah blah . . . .

Ken, I like the formulation that naked life is "life that is the ground of its own worth, which is it say not much worth, actually," which I take to mean without bios, which provides the measure. It's my understanding that Agamben takes the "side" of naked life (or at least forwards it as the underdog to champion) from necessity as a result of the cleave forged by sovereignty. Lil'rumpus was worried about my term "madness," which Tremblebot discerned as my tendency to shunt this through some reference to the Lacanian real. Where I was then going to transition (somehow) is to the homological relation of the homo sacer to the sovereign and a gloss of Agamben's comparative reading of Benjamin and Schmitt. As I gather (I haven't read that chapter in months) Agamben suggests Schmitt and Benjamin were (loosely) in dialogue, and the disagreement involved this locus of anomie: is it containable or circumscribed by the juridical (Schmitt), or is there some powerful, explosive, uncontainable "pure violence" (a sort of disembodied, or multi-bodied rather) that Benjamin said was outside of the juridical but that could be harnessed for political change (revolution). I need to get the language of this disagreement more precise, but as I understand it the argument hinges on a dialectical relation between the law and violence—where the law is understood as an instituting and regulating structure (e.g., the father function in Lacan-o-speak) and "violence" is disruptive, uncontainable, er, energy or life-force or, well, death-drive or aggression. Held in tension the currently "political system" works quite effectively, but when they are caused to collapse Agamben suggestions that "the political system transforms into an apparatus of death." By madness I mean mania in that Greek sense (I've been reading Plato, you see): chaotic ecstasy that can lead to beauty as much as harm—the ecstasy of belonging that can lead to joyful murder. I tend to think of a film like War of the Worlds, a violent and exciting tantrum, and serving up a celebration of the apparatus of death promised my collapse of the norm into the exception.

Ken, I like the formulation that naked life is "life that is the ground of its own worth, which is it say not much worth, actually," which I take to mean without bios, which provides the measure. It's my understanding that Agamben takes the "side" of naked life (or at least forwards it as the underdog to champion) from necessity as a result of the cleave forged by sovereignty. Lil'rumpus was worried about my term "madness," which Tremblebot discerned as my tendency to shunt this through some reference to the Lacanian real. Where I was then going to transition (somehow) is to the homological relation of the homo sacer to the sovereign and a gloss of Agamben's comparative reading of Benjamin and Schmitt. As I gather (I haven't read that chapter in months) Agamben suggests Schmitt and Benjamin were (loosely) in dialogue, and the disagreement involved this locus of anomie: is it containable or circumscribed by the juridical (Schmitt), or is there some powerful, explosive, uncontainable "pure violence" (a sort of disembodied, or multi-bodied rather) that Benjamin said was outside of the juridical but that could be harnessed for political change (revolution). I need to get the language of this disagreement more precise, but as I understand it the argument hinges on a dialectical relation between the law and violence—where the law is understood as an instituting and regulating structure (e.g., the father function in Lacan-o-speak) and "violence" is disruptive, uncontainable, er, energy or life-force or, well, death-drive or aggression. Held in tension the currently "political system" works quite effectively, but when they are caused to collapse Agamben suggestions that "the political system transforms into an apparatus of death." By madness I mean mania in that Greek sense (I've been reading Plato, you see): chaotic ecstasy that can lead to beauty as much as harm—the ecstasy of belonging that can lead to joyful murder. I tend to think of a film like War of the Worlds, a violent and exciting tantrum, and serving up a celebration of the apparatus of death promised my collapse of the norm into the exception.

Ok—I should write all this in the essay instead of in the blog. I hie me to WP.